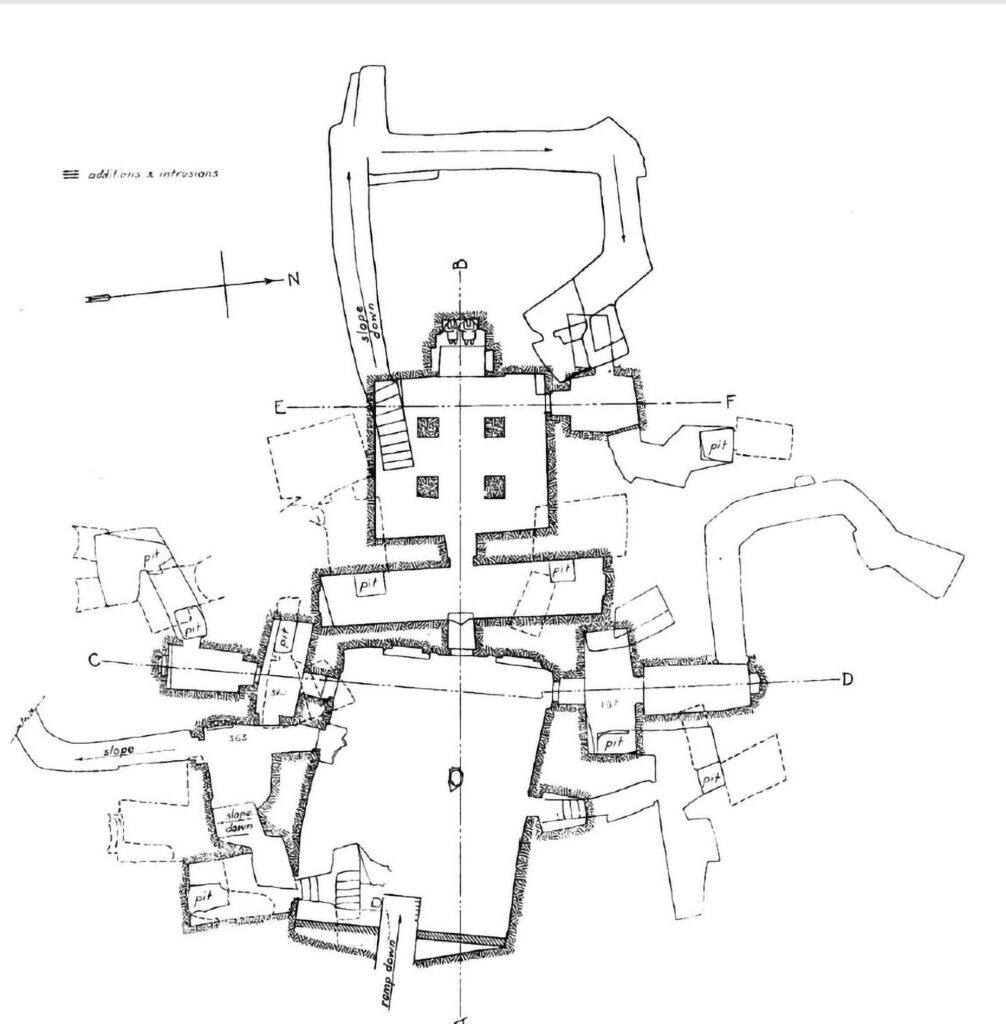

Localizada na colina de El-Khokha Necrópole Tebana dos Nobres em Luxor, está o complexo funerário de Neferhotep. Situado em uma localização privilegiada, próximo à rota processional que conduzia ao templo mortuário de Hatshepsut, Deir-el Bahari, na bela festa do vale. Ele é composto por seis tumbas (TT49, TT187, TT362, TT363, Kampp 347 e Kampp 348) associadas à tumba de Neferhotep (TT49). Membro da elite tebana durante a XVIII dinastia, Neferhotep foi um alto sacerdote do templo de Karnak. Sua família havia servido Amon por pelo menos quatro gerações. Seu prestígio era tamanho que ele possuía diversos títulos, como “grande amon”, “escriba”, “supervisor da Neferut”. Provavelmente, ele desempenhou um papel de grande importância no restabelecimento da ortodoxia tebana após o período amarniano.

O desenho arquitetônico da tumba é característico do final da XVIII dinastia (tipo VIb da classificação de Kampp 1996). Sua decoração é muito bem executada, o que serve para comprovar o prestígio de seu dono (PEREYRA, 2006). No vestíbulo de sua tumba, é preservado o cartucho do faraó Ay, que permite atribuir a tumba ao seu breve reinado (1327 a.C. - 1323 a.C.).

A tumba de Neferhotep é conhecida desde as primeiras décadas do século XIX, quando um habitante da região escavou um buraco e acabou entrando na tumba, danificando uma das estátuas de nicho. Após esse evento, a entrada da tumba se tornou mais acessível quando Robert Hay identificou sua fachada em 1826 e limpou o pátio, abrindo a porta original (PEREYRA, 2019).

Desde então, a tumba recebeu a visita de viajantes que, como precursores da egiptologia, realizaram as primeiras pesquisas sobre o local. Inúmeros visitantes como Jean-François Champollion, Ippolito Rosellini, James Burton, Nestor l’Hote, John Gardner Wilkinson e Émile Prisse d’Avennes deixaram suas anotações e desenhos sobre a tumba durante estas primeiras décadas após sua redescoberta. Estas acabaram tornando-se cruciais para os estudiosos, pois ao longo de dois séculos, o monumento sofreu danos irreparáveis (Ibdem).

Almost a century later, in 1999, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities granted the concession to study the funerary complex to Prof. Dr. Violeta Pereyra, who initiated the Neferhotep Project. The project was originally the responsibility of the University of Tucuman but was later transferred to the University of Buenos Aires. During its development, several international teams joined the project, such as restorers from the Colone (Germany) and archaeologists from the University of Chieti and Pescara and the National Museum – UFRJ. Numerous studies were carried out by the many teams involved.

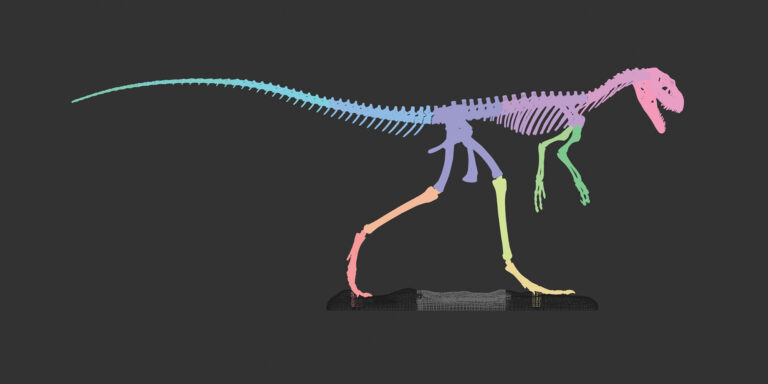

In terms of acquiring digital files, the team from the National Museum, which started the project in 2014, worked on several fronts, such as three-dimensional digitization of the tomb’s archaeological materials, epigraphic drawing using digital epigraphy of the tomb’s walls, three-dimensional digitization of the tomb’s niche statues, and three-dimensional printing of these.

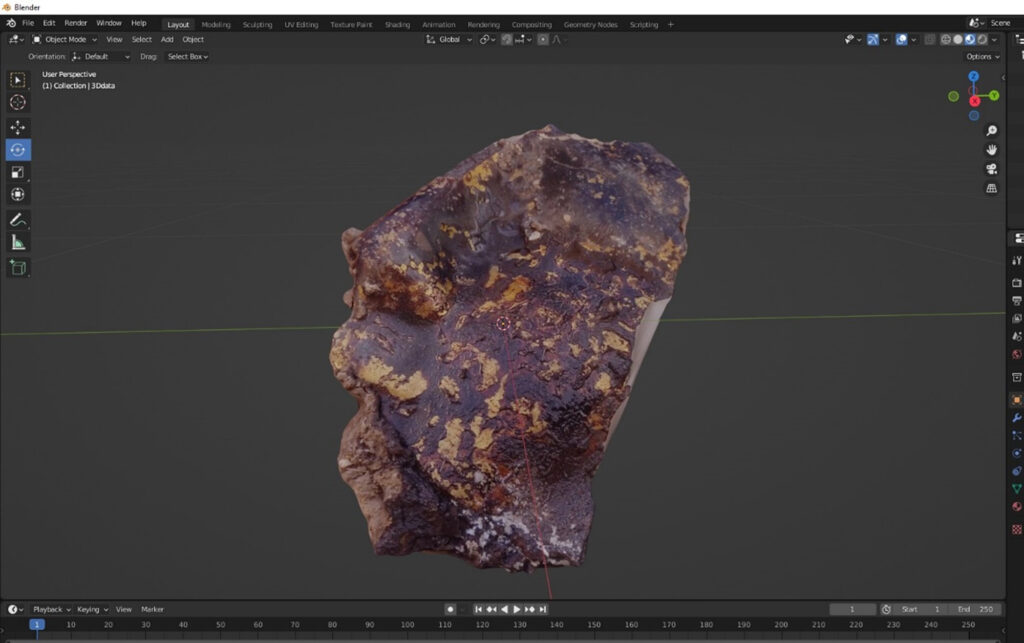

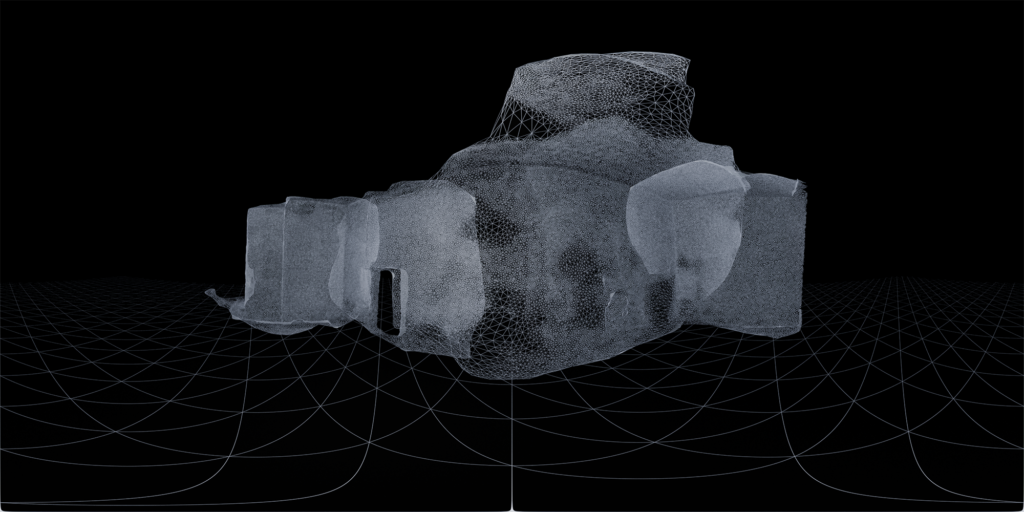

The materials have been digitalized three-dimensionally in different ways. In the 2020 to 2023 campaigns, 3D photogrammetry methodology was used. This is a technique that uses photos from different angles of the object to generate a point cloud and then a textured 3D model. This was done in a photographic studio, while the archaeological materials were carefully rotated on their own axis. The camera used was a Canon 7D with an 18-135 mm lens. The files were processed in the Metashape Agisoft Photoscan software and exported in OBJ format.

For the 2024 campaign, the methodology was changed. During this campaign, the archaeological materials were scanned in 3D with a white light scanner (SC Creality model) with an accuracy of 0.5 mm. A turntable was used to rotate the artifact while it was being scanned in 3D. The scanner works by projecting a white light onto the artifact and then moving it, which allows us to assemble the 3D model using a camera attached to the scanner. First, a point cloud is generated, which is converted into a textured 3D model using the scanner’s own software, CR Studio.

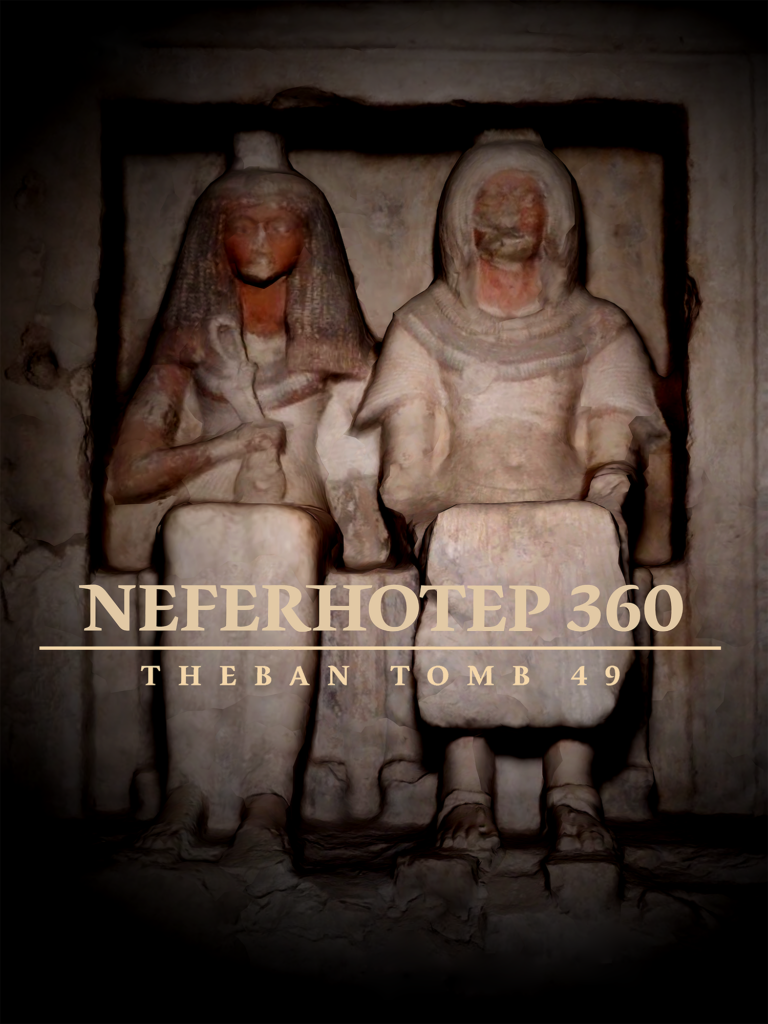

The photogrammetry technique was also used for the three-dimensional digitization of the niche statues in Neferhotep’s tomb (TT49). Subsequently, a 3D model was generated in OBJ and SLT format, which was 3D printed on a filament 3D printer (K1-Max) using PLA – white filament.

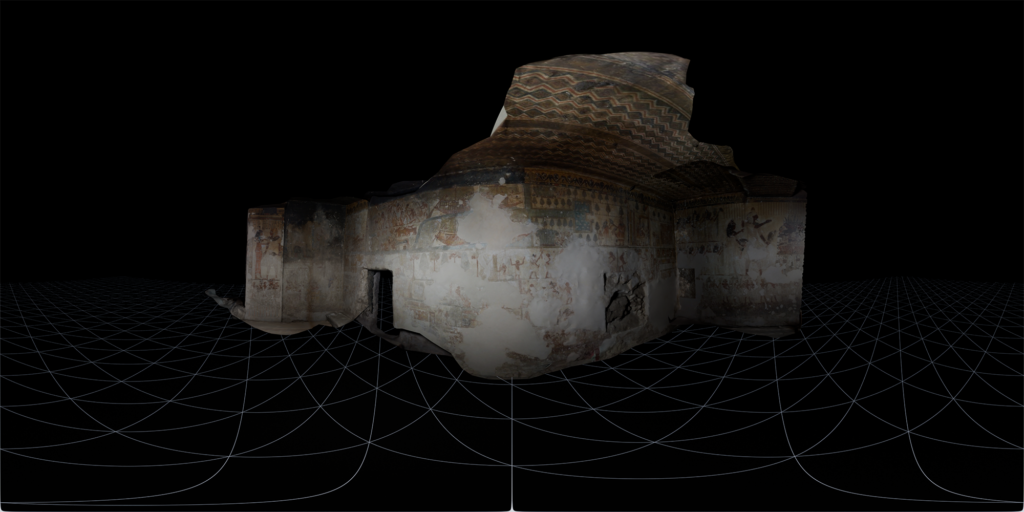

In order to document the work carried out in the 2023 campaign, a series of 360º videos of the work carried out in the tomb was also recorded. For this work, a GoPro 360 Max was used with a tripod in various places in the tomb. To complement this work, a series of photos were also taken with the same camera from the same places in the tomb. This material was then compiled into a VR experience of the tomb.

Neferhotep 360

The purpose of the Neferhotep 360 film was to publicize the research processes of the Brazilian team at TT49 through immersive media: a 360-degree video experience. In this way, the aim is to transport the viewer inside the tomb, creating involvement with both the space and the content presented. 360-degree photos and videos are projections of a spherical image onto a flat image, distributed in an equirectangular grid (Figure 10). In this way, it is possible to create the perception of immersion and displacement in space, a perception that adjusts according to the rotation of the viewer’s head, as illustrated in Figure 11.

The video script is based on the aspects of the research being carried out, as described above, and is guided by Sérgio Azevedo’s narration. To bring these studies together visually in the narrative, specific techniques from each media were used, based on the images produced in the tomb. The creation had interdisciplinary characteristics, and the development method adopted was iterative—both in the elaboration of the narrative, with systematic consultations with the researchers about the images and adaptations, and in the testing of the material using the glasses during the process of assembling the experience.

The film was edited in Adobe Premiere by Luiz Velho and Bernardo Alevato at Visgraf, at IMPA (Institute of Applied Mathematics). The film was edited using the software’s new native tools for editing 360-degree videos. In addition, the Mettle Mantra plugin was used to manipulate the perceived proximity of objects. Although the editing was carried out in a conventional editing program, it is important to note that editing a 360 film differs significantly from editing a traditional film. As Munsterberg (2018) discusses about attention in cinema, the “close-up” effect is provoked in other ways, since there are no defined frames. Being immersed in the image, the viewer is guided by small cuts of interest in certain locations, which are defined by the play of light, sound, and movement, stimulating the rotation of the head. It should be noted that very fast cuts and camera movements can cause discomfort, so the planning sought to simplify the appreciation of the images, using predominantly frontal focus (BRILLHART, 2016).

With the intention of arousing and directing attention, one of the resources used was the graphic signaling of specific areas of the video, synchronized with the narration. To do this, Adobe After Effects and Blender software were used in the videography process; the latter was also the key resource for processing and creating visual material from photogrammetry. Other tools, such as Adobe Photoshop for processing 360 photographs and removing shadows and Adobe Illustrator for creating graphics, were equally important. Google Earth Studio was used to communicate georeferencing information.

During 2024, the experiment was presented to the public on several occasions, such as the National Museum’s IX Egyptology Week (SEMNA), the National Museum’s Girls with Science Project, and the 3rd National Mathematics Festival, when around 1,000 people watched the video and learned about the development and study processes involved in the project.

Referências

BRILHART, J. In the Blink of a Mind — Attention, 2017. The Language of VR. Disponível em: https://medium.com/@brillhart/in-the-blink-of-a-mind-attention-1fdff60fa045#.nm7itb3gk

CHAMPOLLION, J. F., 1844/1973. Monuments de l’Égypte et de la Nubie d’après les dessins exécutés sur les lieux sous la direction de Champollion-le-Jeune et les descriptions autographes qu’il en à rédigées. Notices descriptives, III. Institut de France, Imprimerie et Librairie de Fermin Didot Frères, Paris. Repr. de la publicación de 1844-1879: Éditions des Belles Lettres. Collection des Classiques Égyptologiques. Genève, 1973.

DAVIES, N. de G., 1933. The Tomb of Nefer-hotep at Thebes. 2 vols. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

GARDINER, A. H. & WEIGAL, A. E. P., 1913. A Topographical Catalogue of the Private Tombs of Thebes. London: Bernard Quaritch.

PEREYRA, M. V.; ALZOGARAY, N.; ZINGARELLI, A.; FANTECHI, S.; VERA, S. VERBEEK, C.; GRAUE, B.; BRINKMANN, S., 2006. Imágenes a preservar en la tumba de Neferhotep. Tucumán: Facultad de Artes, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán.

PEREYRA, M. V., 2015. “Images of Power in Neferhotep’s Tomb: Between Tradition and Renovation.” En: A. Jiménez Serrano; C. Pilgrim (eds.), From Delta to Cataract. Studies Dedicated to Mohamed el-Bialy. Leiden – Boston: Brill, pp. 202-217.

PEREYRA, M. V.; BONANNO, M.; CATANIA, M. S.; IAMARINO, M. L.; OJEDA, V. C.; CORDEIRO, E. S. N.; LOVECKY, G. A., 2019. Neferhotep y su espacio funerario I. Ritual y programa decorativo. Buenos Aires: IMHICIHU – CONICET.

ROSELLINI, H., 1834. I Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia disegnati dalla spedizione scientifico-letteraria toscana in Egitto: distribuiti in ordine di materia interpretati ed illustrati dal dottore Ipolito Rosellini, t. II. Monumenti civile. vol. 2. Tavole M.C. Disponible en: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/rosellini1834bd4_2.

MÜNSTERBERG, H., 2018.. In Xavier, Ismail. A experiência do cinema (Portuguese Edition) (2018). Paz e Terra. Kindle Edition.