The activities reported here are part of the author’s doctoral research in the Post graduate program in Archaeology at the National Museum/UFRJ and were supported by the Digital Image Processing Laboratory (LAPID), also based at the National Museum, as well as funding from a CAPES scholarship.

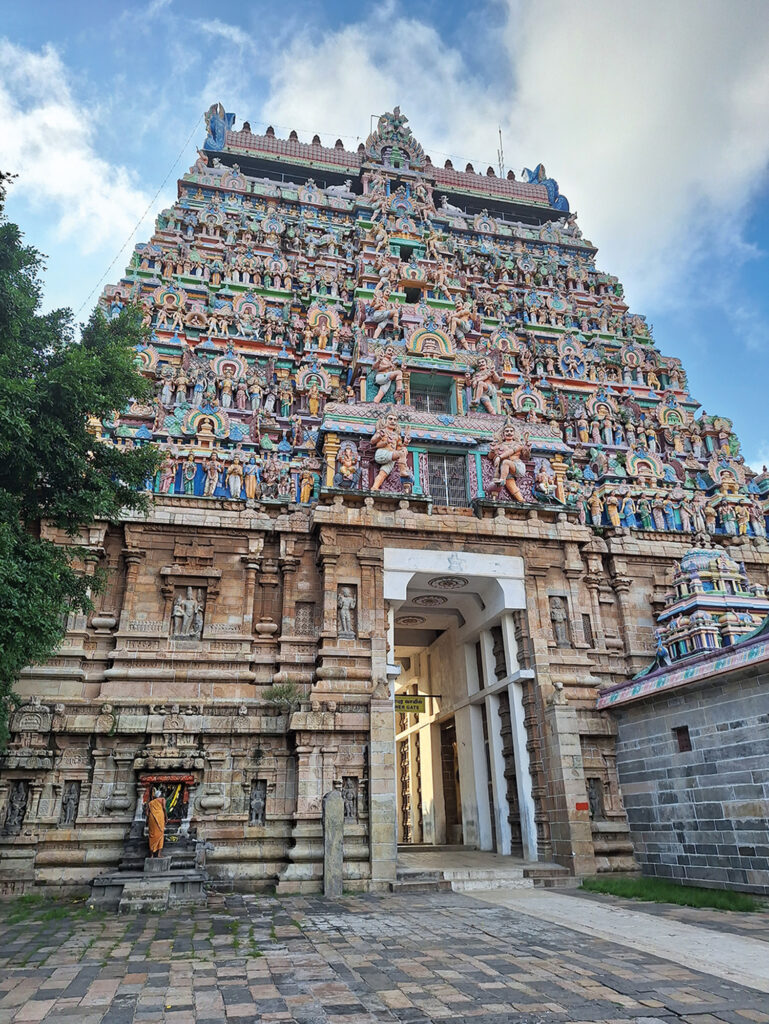

Thillai Nataraja is located in the city of Chidambaram, which is part of Cuddalore district in the state of Tamil Nadu in the southern region of Indian subcontinent. The city is 245 km from Chennai (the state capital). The temple is part of the history of southern India; it is a material witness to religious disputes, power struggles, and political discourses. Literary evidence, both Sanskrit, with the Chidambara Māhātmya, and Tamil, with the Kovil Purāņam, indicate that the sanctity of the shrine dates back to the time of Patañjali, the author of the Yoga Sūtra from the 2nd century BCE. The Tamil poetic work Tirumandiram, from the 2nd century CE, places the shrine’s antiquity in the 5th century BCE. However, when analyzing the structures currently present in the temple complex, none can be dated before the late Chola period (1070-1279 CE).

Currently, the temple complex occupies an area of 50 acres (approximately 202,343 m2), with its entire extension enclosed and featuring four large pyramidal gates (gopura), each built facing a cardinal point, separating religious spaces from everyday life. The monumentality and colors of a gopura stand out among the houses and buildings of Tamil Nadu. The low buildings and wide streets create a landscape that integrates the vibrant colors of the gates (gopuras).

As one of the main elements of South Indian temples, the gopuras are characterized as Dravidian architectural style. They are gateways that can reach monumental proportions. They are usually built with a stone base and brick structures supported by pillars. Typically, their shape is pyramidal, and at the top, they feature a dome. The external walls are covered with sculptures that may or may not be painted.

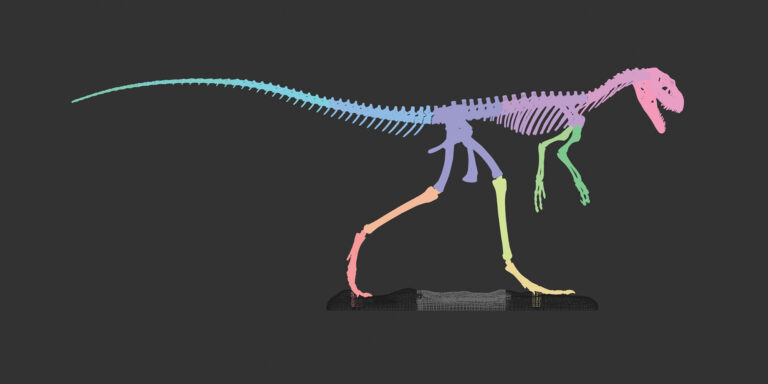

In this research, we focus on the representations of the 108 dance movements (Karaṇas) of Shiva’s Tandava dance that are found on the inner walls of the gateways (gopuras. These movements are described in the Nātyaśāstra, recognized as the codex of Indian performing arts, dated between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE.

At the beginning of Chapter IV, “Tāṇḍava Nṛtya (Description of the Tāṇḍava Dance),” Bharata Muni (author of the Nātyaśāstra) explains how dance was incorporated into the repertoire of nāṭya (a performing art that comprehensively includes music, dance, and drama). Once the god Brahma finished composing the first nāṭya play, titled Amṛta-manthana (The Churning of the Ocean), he asked Bharata to prepare it for performance before the god Shiva. The performance took place in the Himalayan region and was attended by various celestial beings in the audience. At the end of the night, Shiva was very pleased with everything he saw. He said it reminded him of his dance and asked the sage Tāṇḍu to teach it to Bharata so he could include it in the repertoire of performing arts. From there, the chapter continues describing the details of this dance. We are introduced to the 108 Karaṇas (dance movements), 32 Aṅgahāras (choreographic sequences), and other relevant elements for dance practice and performance. The Karaṇas (dance movements) are defined in the work as: hastapādasamāyogo nṛtyasya Karaṇaṃ bhavet | śl 4.31.

In our translation: “The combination of hand and foot movements in a dance is called Karana.”

Between September 2023 and November 2023, as part of our field research, we conducted 3D capture of some representations for research and creation of digital objects. We used the Polycam application on a Samsung A54 mobile phone. We observed that the ability to use a phone as primary equipment facilitates both mobility and acceptance for the development of a work. Since it is rendered virtually, it is possible to analyze the capture result within minutes. Actions can be taken directly in the field, saving time and ensuring better quality of final material. Points of concern include spatial limitations; in our case, sculptures located at very high positions were not easily accessible. Technological challenges such as internet access and battery consumption were also noted. The temple had coverage only in certain areas. As a strategy, we captured three to four statues and then moved to a point where we could send them for processing. This process consumed a lot of battery, which was easily resolved with a powerbank. We conducted the same work in other temples in Tamil Nadu using the same method, which proved to be extremely efficient.

The material obtained here, in addition to integrating the author’s doctoral thesis research, may also be included in scientific dissemination materials in alternative media coordinated by LAPID. •