The Imperial Palace of São Cristóvão, home of the National Museum since 1892, is one of the most important architectural monuments in Brazil and constitutes a significant collection under the institution’s care. Researchers at the Digital Image Processing Laboratory (LAPID), based in the Museum’s Department of Geology and Paleontology, focus on the digitization, modeling and prototyping (3D printing) of the institutional collection for scientific research and the production of support material for educational activities and exhibitions. Therefore, the Palace has always been among the collections included in the Laboratory’s activities.

Unfortunately, this valuable scientific and cultural heritage was severely impacted by the large fire in September 2018. In the subsequent restoration work, previously created three-dimensional archives, as well as new archives produced post-fire, served as support in the restoration of the Palace and its collections. They also played a role in implementing immersive experiences, such as providing spaces accessible through virtual reality. Here, we present some architectural elements digitized by the LAPID team and discuss the current and future uses of these archives.

The Imperial Palace of São Cristóvão

Originally built as a private residence “Chácara do Elias”, the building located in what later became known as “Quinta da Boa Vista” was gifted in 1808, along with the entire area, to the Portuguese royal family, who had recently relocated to Brazil. The monarchs intended to transform the Palace into a space for community engagement. Thus, the royal residence became a model of civility in society, particularly concerning etiquette and other courtly protocols (Dantas, 2007). To adapt the property to the needs and luxuries of royalty, matching the grandeur of Portuguese Palaces, it underwent several adaptations and modifications. These continued throughout the royal, imperial, republican, and modern periods. In 1892, it became the headquarters of the National Museum,(Azevedo, 2007), a date that symbolizes the change from being identified as “Paço de São Cristóvão” to being recognized as the National Museum.

The building is an example of the neoclassical style, reminiscent of European buildings such as the Palace of Versailles, located in the city of Versailles, France, and the Royal Palace of Ajuda, now the National Palace of Ajuda, in the city of Lisbon, Portugal. The presence of statues of gods and the grandeur of the building, with its facade featuring architectural elements of the Italian Renaissance, serves as a reminder of a part of our country’s history. In recent times, under the National Museum Revitalization Program, the building was undergoing an extensive restoration project, including roofs, facades, and several internal areas and facilities that had already been restored when it was hit by the 2018 fire. The building is currently undergoing a new restoration project and is expected to be made available to the public soon.

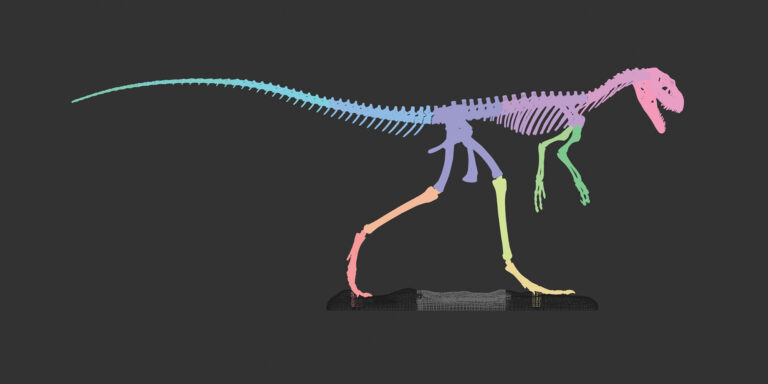

The first digitization efforts of parts of the building began before the fire. In 2008, during the development of the Virtual Dinosaurs Project, internal and external parts of the Palace were digitized, modeled, and made available on the internet (Monnerat et al., 2010). The work intensified during the post-fire collection rescue process (Azevedo et al., 2019; Carvalho et al., 2021) and in the following years.

In recent decades, we have witnessed the development of various 3D scanning technologies aimed at reproducing parts of the cultural heritage for study and public availability. These 3D replicas strive to faithfully reproduce tangible objects, capturing their general and detailed shapes, surface textures and colors. These models serve as valuable study and observation tools, perpetuating cultural heritage through dissemination. 3D scanning technologies have become indispensable in reproducing architectural structures, allowing for the study of historical, cultural, and morphological characteristics of structures on a scale proportionally larger than human scale.

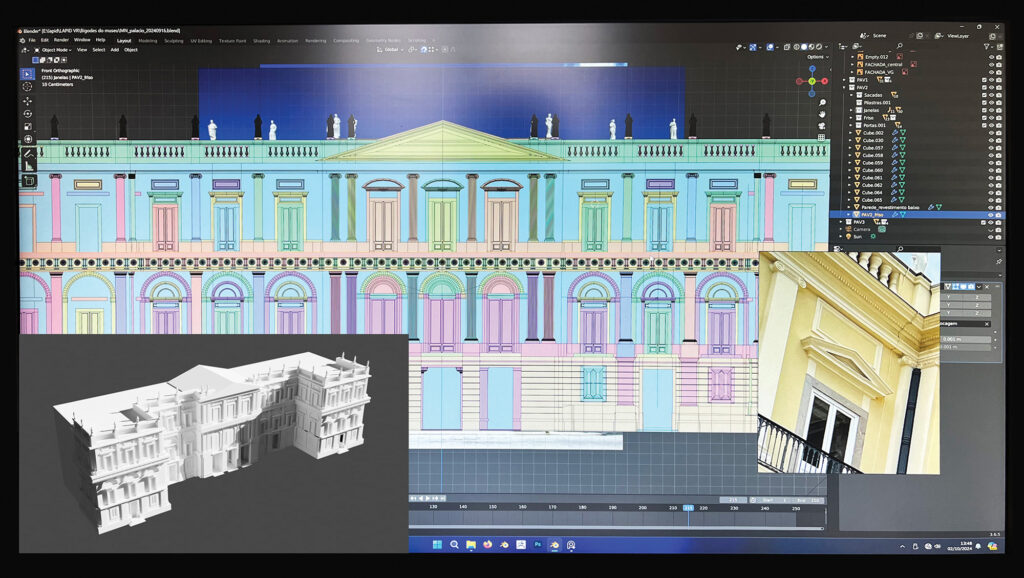

In addition to the historical and scientific collection, the fire also severely damaged the historic building that housed the Museum, the former official residence of the imperial family. The fire compromised the internal structure and facades, causing the collapse of the roof and the slabs that made up its three floors. The use of three-dimensional technologies and methodologies, an area of expertise of the LAPID team, played a crucial role in the process of rescuing the Museum’s scientific collections and its building. The modeling process of the National Museum Palace began in 2024, driven by the need for a scaled physical model to serve as a reference for future studies and projects developed within the laboratory.

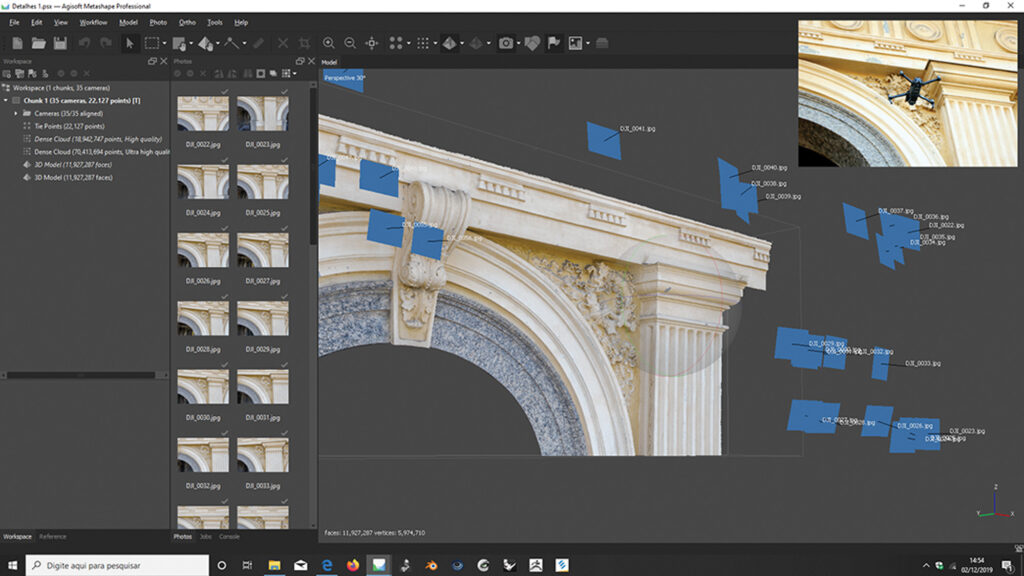

Initially, different areas of the building’s facades were captured using digital cameras and a drone (DJI Mavic 2). In addition to the previous surveys, we also captured several photos of the facade’s details using smartphone devices. These photos were combined to generate a digital reconstruction of the building’s elements using photogrammetry algorithms, a technique that extracts information from georeferenced images to create a three-dimensional model. Additionally, much of the photographic material recorded served as a visual reference for the Palace’s modeling work, where adjustments to perspective and images overlays were necessary to obtain elements of the structure as faithfully as possible. It was also necessary to acquire the ground plans of the three floors to indicate the positions of the building’s structural elements.

Once the reference images were obtained, we could begin modeling the Palace. The program used was Blender, an open-source software for digital modeling and sculpting, UV mapping, rigging, animation, and other three-dimensional tasks. This program was chosen over other similar programs due to its accessibility and user-friendly platform, covering all stages of 3D modeling. The Palace was modeled starting with the ground plan, followed by the facade, with elements of each floor being inserted in turn: decorated portals and gates, walls with different textures, balconies, windows, arches, neoclassical columns, pediments, and other elements. The final model included the central facade and the north and south towers of the Palace.

With the digital model ready, it was possible to develop some physical models on a reduced scale using additive manufacturing technologies (also known as 3D printing). The materialization process, conducted using 3D prototyping technologies, is based on the successive layering of material, in this case, PLA, a biocompatible and biodegradable thermoplastic derived from renewable resources such as cornstarch or sugar cane. The material layers are superimposed following the 3D file read from the STL extension (an acronym for stereolithography, also known as “Standard Triangle Language”), which consists of creating a model composed of a series of connected triangles that geometrically describe the surface of a 3D model.

In addition to the scale models of the Palace, 3D scanning and prototyping technologies functioned in this project as a receptacle for the memory and visibility of a monument that represents a part of Brazilian history. The space created through architecture has the power to influence and dominate our spirit: its dimensions consider not only the spatial value but also the light and shadow, color, horizontal and vertical lines of the environment, all of which are perceived and studied when we examine the morphology of a building (Zevi, 2009). By analyzing the physicality of what was built, we are disclosing the social memory of a certain era, identifying the customs of the sovereign and his relationship with the residence through the reading of the spaces delimited by the building (Dantas, 2007). That said, this project is ongoing, with room for future work, such as modeling the internal structures of the Palace, digitizing details in specific areas, and extending the project to areas beyond those already prototyped.

The “Muses” of the National Museum

In classical mythology, the term “muses” refers to the nine spring entities, daughters of Mnemosyne (goddess of memory) and Zeus, who were believed to inspire artistic and scientific creation in men (epic and lyrical poetry, history, traditional and ceremonial music, tragedy, comedy, dance, astronomy, and astrology). Their homes were usually near springs and streams, but they also frequented Mount Helicon and often accompanied Apollo, God of the arts. The places dedicated to the nine muses were called “mouseion”, a term that later gave rise to the word “museum”.

The term “muses” is still commonly used to designate the statues that decorate the main facade of the Palace of São Cristóvão. Although these sculptures do not technically represent the classical muses for the most part, they are popularly known as such. The National Museum Palace has a set of 31 centuries-old sculptures made of Carrara marble, each weighing between 200 and 300 kilos. After the fire in September 2018, this entire collection underwent a restoration process, involving technical cleaning procedures, consolidation of the marble, internal structural reinforcement, and filling of small cracks. The restoration of these pieces resulted in the construction of full-scale replicas that are currently located on the parapet of the historic block of the main facade of the Palace. The restoration work was carried out by the “Museu Nacional Vive” Project, and a short video about the process entitled “Restauração das esculturas do Paço de São Cristóvão” (Restoration of the sculptures of the Paço de São Cristóvão) is available on the YouTube platform (source: museunacionalvive.org.br/esculturas). Eight of them (Bellerophon, Ceres, Cybele, Hygieia, Luna, Mercury, Nymph and Orpheus) were exhibited in the Museum’s main garden, where they were digitized by the LAPID team.

For the process of digitizing and reproducing the statues, we opted for an image capture method (photogrammetry) due to its accessibility and efficiency. In this case, however, instead of using professional software, we decided to test a simpler solution based on a smartphone application (Polycam) to assess the feasibility of using these alternative methods. A sequence of photographs was taken around the eight statues that were open to the public in the main garden of the Palace, in front of the main facade of the National Museum building. This material was then processed using the Polycam application.

After processing the models, adjustments were needed to the mesh to correct any flaws in the surface of the model, especially in the upper part of the statues, due to the difficulty in obtaining a satisfactory angle due to the height of the sculptures. Bases for the statues were also modeled in the Blender software, containing information such as the name of the entity and the logos of LAPID and the National Museum. After finalizing the 3D model, it was sent for 3D prototyping. The printer used was the Creality K1 Max series, and the filament used was Hyper PLA in white, to maintain the chromatic similarity with the original sculptures.

The Palace Gardens and its statues

“Quinta da Boa Vista” is considered one of the largest urban parks in Rio de Janeiro and also houses the Imperial Palace of São Cristóvão. Over the years, it has undergone a series of modifications, with the most significant landscaping carried out by Auguste François Marie Glaziou (1833-1906) between 1866 and 1869. Glaziou transformed the park into a romantic European-style landscape, similar to Versailles, featuring lakes, statues, fountains and other ornaments (Dantas, 2007). A straight avenue, “Alameda das Sapucaias”, was also created to lead visitors from the park to the Palace. Upon arriving at the Palace, visitors are greeted with the sight of two culturally and historically significant statues – those of Emperor D. Pedro II and Empress Leopoldina.

The statues of Dom Pedro II and Empress Leopoldina

The statue of Dom Pedro II is a bronze sculpture by Jean Magrou, designed by Heitor da Silva Costa, and placed on a granite pedestal. It was inaugurated in December 1925 on the centenary of the emperor’s birth (source: monumentosdorio.com.br). The statue of Empress Leopoldina is also a bronze sculpture, created by Edgar Duvivier, and was inaugurated in 1996 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Leopoldina’s birth. The monument depicts the Empress accompanied by her two children: Pedro de Alcântara (D. Pedro II, on her lap) and Maria da Glória (D. Maria II, at her side).

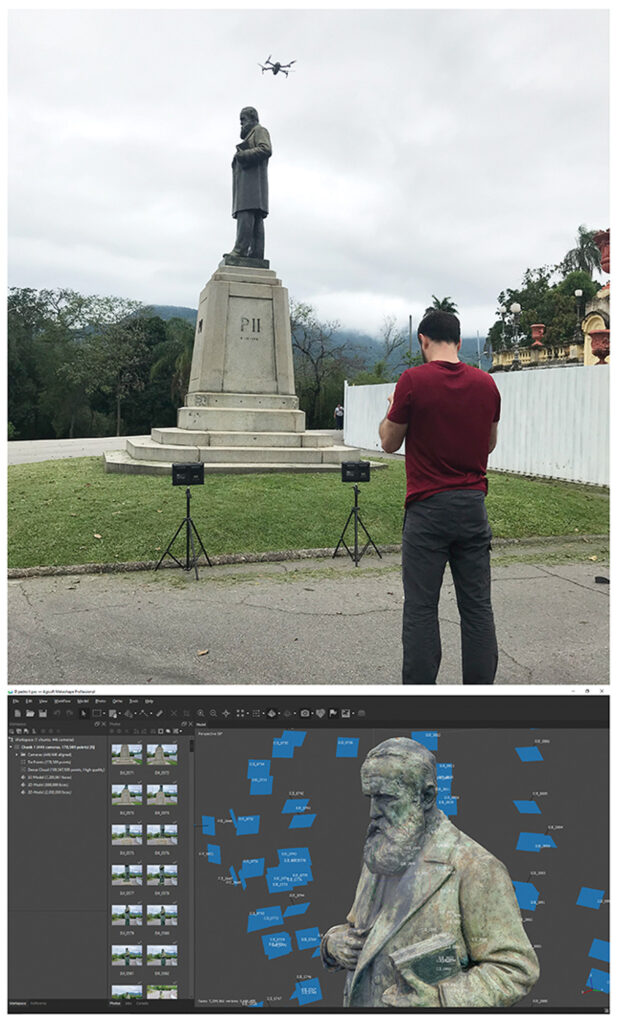

The work of digitizing the statues began in the second half of 2019, carried out by the LAPID team. Photogrammetry was chosen for this capture due to the height of the statues and the accessibility of their upper areas and location, as both sculptures were in the middle of a public promenade. The images for both statues were captured using a DJI Mavic 2 Pro drone. Additionally, LED reflectors were used for the lower areas of the statue of D. Pedro II, which lacked adequate natural lighting.

After the photography stage, the images were processed using Agisoft Metashape software, which is dedicated to the entire photogrammetry pipeline. After positioning the images and generating the point cloud and mesh, models were generated in STL format for prototyping. These models were printed in PLA, with the scaled statues of D. Pedro II and Empress Leopoldina measuring 18 cm and 12 cm, respectively. To achieve a resemblance with the original bronze statues, the prints were painted with matte acrylic varnish in a rustic brown color.

Other digitalizations

In addition to the pieces mentioned above, the LAPID team also worked on the three-dimensional scanning of other architectural elements of the São Cristóvão Palace, such as facade ornaments (e.g., lion, coat of arms) and details of some structures like doors and windows. As with the statues, these architectural elements were scanned using photogrammetry. Additionally, the main entrance doors of the Palace, with their meticulous decoration, were particularly subjected to this technique, focusing on smaller details such as the ornaments featuring lion heads, the symbol of the Royal House of Castile. After digitization, these elements were incorporated into the models of the São Cristóvão Palace for future scale prototyping of the monument.

The “Bigodes do Imperador” Project

The “Bigodes do Imperador” (Emperor’s Whiskers) Project emerged in December 2022 as a spontaneous, voluntary, coordinated, and plural initiative of museum staff and students from the National Museum. Its main objectives include better understanding the situation of community animals, the dynamics of abandonment in the areas of the National Museum, and testing population control and animal welfare procedures while respecting current legislation.

Following the protocols and recommendations of the WHO, the Municipal Code of Animal Rights and Welfare of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, and several other regulations on the subject, the Project operates by capturing, sterilizing, treating, promoting adoptions, and returning to their areas of origin those animals that are not eligible for adoption.

The Project’s main source of resources come from monthly contributions by members of the National Museum’s social body, external public supporters, social media campaigns, and raffles. “Bigodes do Imperador” currently has an important partnership with a veterinary clinic located in São Cristóvão and the “Bigodes do Bunker” Project, which is responsible for sending some cats from the National Museum for adoption at the Botafogo branch of the famous “Gato Café” establishment.

With the growing awareness of the National Museum community about the importance of the Project, the “Working Group for Community Animals of the National Museum/UFRJ” was established in December 2024. The purpose of this group is to develop and structure procedures that comply with current legislation for the population control and well-being of these community animals. The Working Group has ten employees from the Institution. It is important to emphasize that the initiative is especially important in aligning the National Museum with the guidelines of UFRJ itself, which, in 2012, created the “Working Group for Animals” to centrale referrals and propose procedures for solving the issue of abandoned animals on university campuses.

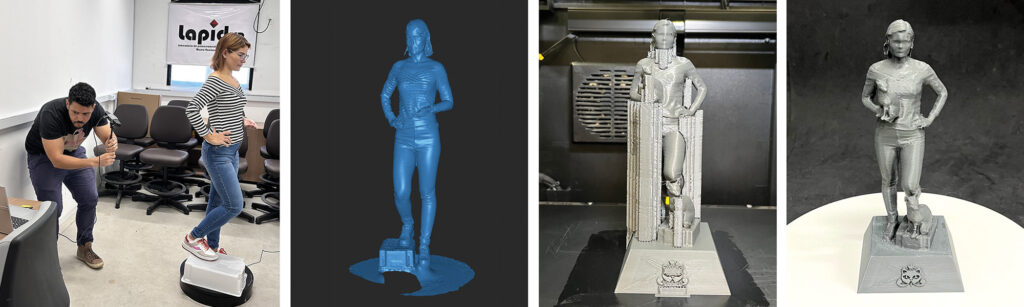

To support this important initiative of the National Museum community, the LAPID team sought to define interfaces of common interest to apply their techniques and equipment to the activities developed by the “Bigodes do Imperador” Project team. The first step in the process was to digitize a human model. We opted for digital scanning using a Creality CR-Scan 01 scanner and a Revopoint automatic rotating platform with a diameter of 500 mm to serve as a basis for the capture. The model was positioned on the platform, and the scan was performed manually, with its readings transferred directly to the equipment’s software. As a working methodology, a sequence of three scans was carried out: one of the whole body, another only of the face, and another only of the torso.

After this step, the scanned file was processed, removing extra point clouds, correcting imperfections in the mesh, and preparing the file to be incorporated into the final project created in Blender software. A base modeled within Blender was added to the statue model, containing the name of the project “Bigodes do Imperador” and the logos of LAPID and the National Museum. Two cat models, obtained from websites that distribute free-to-use 3D models, were also added.

With the statue model finalized, an STL file was generated for prototyping. After a few test prints to check for the best definition and scale, the final prototype was produced on the Creality 3D K1 Max print, using Premium PLA filament in graphite Velvet color. The statue has the following dimensions: 70 x 70 mm base and 170 mm height.

The creation of such a model aims to publicize and support future “Bigodes do Imperador” campaigns, where a collaborator can receive a three-dimensional model of themselves with a cat as a prize.

References

AZEVEDO, S. A. K. (organizador), 2007. Museu Nacional. Ed. Banco Safra, São Paulo, 360p.

AZEVEDO, S. A. K.; GRILLO, O. N.; VON SEEHAUSEN, P.; CARDOSO, G.; LOBO, L. S.; BRANCAGLION Jr., A.; RODRIGUES-CARVALHO, C.; CARVALHO, L. B.; BASTOS, M.; BITTAR, V. S.; REIS, S.; RABELLO, A., PEREIRA, E.; AGOSTINHO, M. B.; AGUIAR, P.; WITOWISK, L.; ZUCOLOTTO, M.E. & LOPES, J., 2019. 3D After the fire. In: J. Lopes; S. A. Azevedo; H. Werner Jr. & A. Brancaglion Jr. (eds.) Seen/Unseen: 3D visualization. 2019. Rio Books, Rio de Janeiro, p. 56-65.

CARVALHO, L. B.; AZEVEDO, S. A. K. ; WITOWISK, L.; MACIEL, B.; GRILLO, O.; CABRAL, U.; SILVA, H. & GONÇALVES, P., 2021. As Coleções Paleontológicas…/The Paleontological Collections… 84-97. In: C. Rodrigues-Carvalho; L. Carvalho; G. Cardoso & S. Reis. 500 Dias de Resgate: Memória, coragem e imagem/500 days of Rescue: Memory, courage and image. Série Livros Digital, 22, Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, RJ. (ISBN: 978-65-5729-007-1 digital e 978-65-5729-008 impresso).

DANTAS, R. M. M. C. A Casa do Imperador: Do Paço de São Cristóvão ao Museu Nacional. Rio de Janeiro: 2007. Dissertação (Mestrado em Memória Social) – Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

MONNERAT, M. C.; ROMANO, P. S. R. ; GRILLO, O. N. ; HAGUENAUER, C. ; AZEVEDO, S. A. K. ; CUNHA, G. G., 2010. The Dinos Virtuais Project: a virtual approach of a real exhibition. IADIS International Journal on WWWInternet, v. 8, p. 136-150.

Restauração das esculturas do Paço de São Cristóvão, Projeto Museu Nacional Vive, Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QBJg4MJrNq0&t=39s Acesso em: 24/04/2025.

ZEVI, B. Saber ver a arquitetura. Tradução: Maria Isabel Gaspar, Gaëtan Martins de Oliveira. 6ª ed. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes, 2009.