01. Replica’s, copies and facsimiles – Fakes or tributes?

In 1973 Orson Welles directs “F for fake”, the story of Elmyr de Hory (1905-1976), a successful forger specialized in Matisse’s and Modigliani’s, in addition to certain phases of Picasso and other Impressionism and post-Impressionism painters. Established in old age in Ibiza, the artist tried his own path, but found a more profitable way of life, when in 1946 a friend mistakes a copy of a Picasso drawing as original. Elmyr then has the idea of selling the material through the galleries in Paris. Earning little, but consistently collaborating with dealers disinterested in the source of the material, ends up turning counterfeiting into their main activity. He led a gypsy life, obscure, sometimes prosperous, sometimes spartan, passing through several countries and two continents.

The narrative already confused by Welles’ quick cuts, which intersperses fictional scenes with true images, becomes even more fabulous when part of the film is dedicated to Clifford Irving, Elmyr’s biographer and author of “Fake!” (Irving, 1969), a book that tells the life of the painter counterfeiter, who proved to be a best seller, and whose home is also the Spanish island. Perhaps enthusiastic about the ease way the arts world absorbed and legitimized lies, Irving himself becomes a forger by securing a sumptuous editorial contract by tampering the handwriting of reclusive industrialist Howard Hughes, stating that the writer was preparing a publication narrating your memories. In the end, Irving is unmasked by the magnate, spending some time in prison.

What stands out in the film, in addition to the improbable encounter of two talented counterfeiters, is the fate of the works created by Elmyr on camera attesting his skills. The drawings after being made are mercilessly burned in the fireplace of his residence. The flames in liturgies purify and separate the chosen from the infidels, the sacred from the profane. For what is done for the sole purpose of deceiving and causing misunderstanding, of deluding. But was this the end they deserved? At this point the story of the forger meets the story of the fire.

On September 2, 2018, the fire suffered by the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro practically turned a part of the institution to ashes. In this story of fire and loss, we don’t advocate that imitations by great masters or copies should gain the same status as their originals, especially when the intent is to scam. However, these examples of mastery could not have any other value, or be aligned with a winding and blurred line in the History of Art, which encourages copying and imitation as part of the formation of an artist, but that at some point in the emergence of capitalism and speculation around objects with historical or artistic value come to be questioned? So when we talk about the loss and the mourning of an institute for a collection, the act of copying becomes an act of tribute.

02. The role of a digital collection

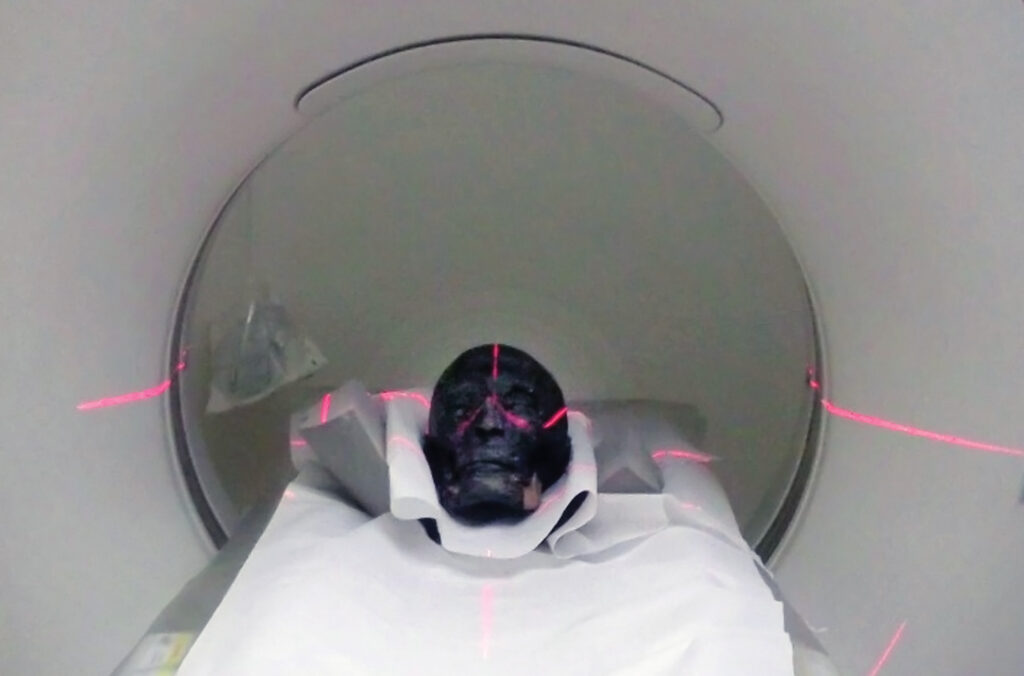

For 18 years, researchers from three different Institutions in Brazil: the Brazilian National Museum-MN, the first scientific institution in Brazil (1818), the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation-MCTI and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro – PUC-Rio, have worked together on the digitization and materialization of 3D printed replicas of the MN collection. During this period, hundreds of pieces have been 3D scanned from the vast collection through various non-destructive image technologies such as computed tomography and 3D scanning. This partnership among the labs gained also the support of a medical image private clinic (Clínica de Diagnóstico por Imagem – CDPI), resulting in the crossing knowledge on the obtaining of 3D files that allow researchers to have access to the medical CAT scanners for visualizing hidden structures. The obtained results were better than expected, expanding the project forward to other areas of the MN as the Egyptology.

During nearly 20 years, accompanying the fast technological advances, several 3D technologies have been used on the project, resulting in hundreds of 3D files related to the MN collection, obtaining files from objects from the archaeology, paleontology, anthropology, zoology and other departments of the museum (Lopes et al., 2019). In this context, several replicas for different purposes have been made, such as the replica of an ancient Egyptian head was exhibited besides the original, in order to explain to visitors what could be found inside the wrapped mummy. This kind of replica serves a mere educational purpose and is always shown as a technological replica instead of trying to replace the original that lost his “aura” of authenticity.

When the fire at Museu Nacional occurred on 2018, part of the existing collection in the main Palace was seriously damaged or even lost. All the laboratories located in the palace were drastically impacted, and due to the Museum’s rescue team, which immediately acted in the search and recovery of the collection, many pieces were found and recovered. With the aid of the 3D digital files described above, many pieces are still being recovered, analyzed and sometimes physically and virtually repaired through technologies such as 3D printing and Virtual Reality. But this is an unprecedented situation. For the first time in history, a museum has lost such a large and diverse collection of physical objects, leaving only its digital counterparts. Questions arise about how we protect scientific-cultural heritage and manage a physical and digital archive. Today, these high-resolution 3D models offer the possibility to re-materialize memories and to explore how to add relevant meaning through the act of re-making.

03. The honour to copy

The potential of the copies seems to be born with the production of artifacts in humanity, and remains, later, as a statute to what receive the quality of artistic. For a long time in history, approaching the skill of the master through the exercise of imitation was the guarantee of a passage of solid knowledge. Only after the Renaissance the idea of authorship matured, and artisans are recognized for their particular characteristics of style, while remaining linked to their teachers’ studios and being celebrated as such. Being apprenticed to someone established and experienced seemed to be the natural way to ratify himself as a manipulator of forms. This, at least, until the foundation of schools that offered education in a formal and systematic way.

Imitating is the pragmatic exercise of experiencing the technical and aesthetic challenges of a predecessor with the intention of fixing lessons, taking as a starting point something already attested by the field as relevant. This process is present in practically all civilizing acts, from using cutlery to changing car tires or docking boats. When we watch someone do it, everything is easier. For there are more complex tacit knowledge to be acquired theoretically; either by written or oral sources. Richard Sennett in his book “The Craftman” (2008), tells how complicated it would be to explain the boning of a chicken using words, but how the process can be intuitively internalized when we observe a chef manipulating the knife and the animal. There is a learning curve, but with time and discipline, it is possible to go through it. The author chooses clay, wood and food as the three materials historically chosen for the establishment of bonds of trust and knowledge transfer between master and beginner. Materials according to him, available to almost infinite metamorphoses and that have been with us for millennia.

What is questioned in the publication is the devaluation of the time invested until the acquisition of a specialization in view of the acceleration of the means of production, and of how manual making has come to be considered inferior in view of the fast technologies of the current construction processes. However, even so, the desire to do something well is still maintained today as the noble heritage of work that unites practice and theory through the direct involvement of the body. It is not our aim here to analyze this wear and tear, but to update and remember, which we learn from examples, which we consciously or subliminally try to emulate. So, where do our copy problems begin, if they are an intrinsic part of our affirmation in the world?

For Walter Benjamin (2012), the rupture occurs when capitalism, through the massive exploitation homogeneous the proletarian labor, not only the codes and work procedures of the new industrial order, but also contributes to the suppression of its singularities as an individual. As someone who loses, despite belonging to a collective, a right over his imagination and the way he behaves and does things in the world that would make him unique. This differentiation the system admits as dangerous and subversive. We already know and live the consequences of the different regimes that the 20th century went through trying to deal politically with these divergences. Today we find ourselves mired in late capitalism, which has done little for the workers, but which has incorporated very well, and in a convenient way, the oscillation between devaluing or not something that is or is not unique.

The author himself in the famous text in which he presents the concept of “aura”, already admitted that in essence the work of art has always been capable of being reproducible, whether by disciples, for diffusion or profit. What seems to bother the author is the level of quality and non-distinction that works can have when reproduced by technical means of production. Something would be lost in this process, the author calls it “aura”, but we here, in our thought exercise, will propose that we are also facing the absence of something valued by Sennett, which is the involvement of the body to accomplish something well within a tradition, with an idea defended by Philippe Dubois in his work “L’acte photographique et autres essais” (1990), which we will see below.

Written in the transition from analog to digital processes of photographic production, the French author’s work proposed a reflective synthesis on the fundamentals of language based not on the result – on the potentially infinite copies possible from a single frame and the visual messages embedded in them -, but in its genesis, as the testimony of the relationship of presence at a given moment in time between author and model. The trace of this interlacing, he called the index. To this end, it relied on the work of the American philosopher and semiotic Charles Sanders Peirce, who focused on its meaning, in addition to that of “icon” and “sign”. In short, the indices would be signs, but they maintained some real connection, of physical contiguity with their referent. As a closer example to photography, he uses the tanning of bodies. Exposure to sunlight alters the color of the skin, leaving darkened and other protected parts virgin, just as the emulsion reacts on the paper when the inverted image is captured and negated by the optical apparatus of the machine. We then have a film modified by luminosity, which are light and dark resulting from the act of exposure to it. There is proof of the physical circumstances of that encounter, attested ontologically.

The mark of this absence, which attests to a physical connection in time, bears a strong resemblance to the myths of the emergence of painting and, consequently, of sculpture. Pliny the Elder, Roman philosopher and statesman who lived between 23 and 79 AD, narrates in his work Naturalis Historia (Pliny the Elder, 1961) the fable of the potter’s daughter Dibutades, who is in love with a man who goes on a trip, asks the lover to stay amid the flame candle (we highlight again the presence of the flaming element in the narrative) and a wall to copy its shadow, in order not to forget the silhouette. The story does not end there, because Pliny says that later the potter adds clay to the profile and thus, we have, as an extension, the myth narrator of the arts of molding and three-dimensional modeling.

It is powerful to be able to associate the emergence of registration, representation and art with an act of desire and love in the face of a distance. Mimesis is an attempt at contiguity and the work is an index of an affective lack, or a concrete means of dealing with it. It is created because a void is left. Dubois, takes the opportunity to unite the fable, the imaginary trace of its absence and the time with which we assimilate the losses with the photographic act. We are talking about mourning. Although culturally distinct, during these periods we deal with feelings of sadness, frustration, anger and helplessness, given the fact that we follow, while something dear to us, no more. The photographer’s unique contact with his model (coexistence), the dry cut of the shutter (death) and the time until the image is developed (mourning) will cause a similar result, that of consolation. But it is necessary to cross the latency, the doubt, the risk of the revelation revealing nothing and petrifying ourselves before the emptiness or falling in love with the result.

Between the Medusa that paralyzes when being looked at and Narcissus, that drowns while embracing its reflection, stay in the middle of the path and build a Perseus shield. A healthy and playful way of not immobilizing yourself in the face of finitude. An indirect path to looking at our limitations with a symbolic tool, which metamorphosed the pain and which, as a consequence, allowed something to the world. If the photograph leaves the image, in death, we are left with good memories of the absent (the photo too) and we can invoke ghosts. For Benjamin, one of the processes that contribute to the loss of the aura is the seesaw between the cult value and the exposure value. The bigger one, the smaller the other. The Shroud of Turin is ancient and rarely exposed. What is in the cathedral is a negative image, which makes it possible to see the marks of the body, a representation of the linen, not itself. The almost permanent concealment of the original, apart from exceptions, guarantees a high worship value.

Not having access to the experience index seems to guarantee, according to the German author, a singular connection of space and time, which confirms the maintenance of the aura. Waiting / mourning to contemplate something unique is a path to dreams, fictions and frictions, which can lead to the new and the old simultaneously. It is the dialectic between imagination and reality. The aura, after so many thinkers focused on it, may no longer be in a problem of repetition, or is in the quality of the copy, or even if it comes only from the original, but from invoking that inner path that allows us to fable.

04. A quality of aural presence

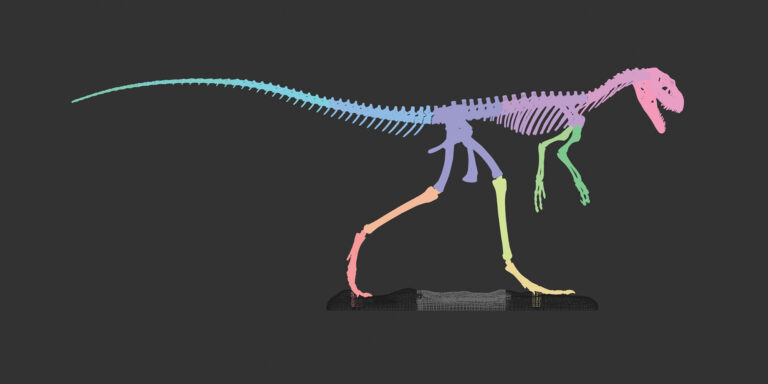

We live in a world immersed in doubles, triples and confusions between negative and positive. The level of distinction between the palpable and the virtual and its unique qualities, today are almost surpassed by the technical quality that allows them to be reproduced. Therefore, the permanence and emanation of the aura may depend much more on our quality of presence, than on things or situations. We risk saying that the aura is an availability before. For example, this article is being written by authors with different backgrounds, bringing together areas of science, design and art. While at some point in the argument copy seemed to us to be inferior, or an artfully derogatory characteristic, in the field of paleontology taking the copy of a fossil, either by manual molding technique, or by the digital and non-invasive methods described here, is demonstrated enormous respect for the original and for his field colleagues. Having the replica of an extinct animal bone is power without shame, manipulating, breaking, building extreme test prototypes and risking preserving, while sharing the experience and providing the opportunity to colleagues who can explore with this model. The copy gains a noble status, because the quality of attention dedicated to it is unprecedented.

In human sciences and poetic creation, it can be a phase of awakening skills, without which we would not reach the maximum level of our virtues. It is known in Art History the forge that Michelangelo executed of the statue named “Sleeping Eros” (1496), whose model originally dates from the 3rd century BC, when he was only 21 years old (Charney, 2015). Having made the copy, with presence and dedication, in a state of aura, technically prepared him and paved the way for a much more ambitious next order, the celebrated “Pietá” (1498-99). Rescuing our caricature Elmyr from the film by Welles, some claim that they bought his works knowing that they were copies, but that they were made with such quality, that they “attenuated” the crime. The forger claimed that his Picassos had to be done in 10 seconds, as Picasso would do them. This dedication to emulating a more successful craftsman has its moral sins, but it also demonstrates enormous respect for a skill that is used as a parameter of mastery. His works are in many collections under other signatures, so some immortality has achieved. As Elmyr himself stated, just leave enough time on the walls of the museums, that sooner or later the false becomes true.

We can offer ourselves an exercise in thinking that may consider aura-related issues at another point, as the value of the replica is becoming more and more plastic. Our problems start when we have direct and explicit access to everything. The world of excess that we inhabit has accelerated our perception so much, that the speed with which we build images (sound, visual, tactile) is without comparison in terms of quality in History, but whose consumption is only comparable with the speed with which they are discarded. The aura disappears with banalization and anesthesia.

When researchers come together and promote, after years of digital documentation of the MN collection, the printing of 3D models made with the ashes of the places close to what they occupied in the institution’s architecture are bringing together all the concepts worked throughout this text. They are unfolding the traditions of recording and passing on knowledge, they are actively working on losses, they are updating philosophical concepts and they are pointing out that the end can be a new beginning when there is affection for what is done. Not by chance, the choice of some reproduced objects and the actions taken on others invoke mourning and erasure.

In this context, several projects arose. One of the experiments was done with a marajoara funeral urn, a society that flourished on the Marajó Island in the Amazon River in the pre-Columbian era, whose original was lost in the fire. A model of one of its faces printed in 3D technology, was covered with sand plus resin used to take molds, which hardens in the presence of heat. After being roasted in an oven, the model was removed, leaving a concave negative similar to the voids in Pompeii after the eruption of Vesuvius, which extinguished the city. An artistic, scientifically oriented piece that sought to emulate the process of disappearing by the fire that ended the fate of its original, personifying the phantasmagoria of this absence. This piece was an experiment carried out in stages of testing for possible developments.

Another gesture occurred on a burnt wood trunk from some structural part of the museum. The object that belonged to one of the many phases of renovation and expansion of the construction has a conserved part and its rest burned. Using a computerized milling machine, he received the excavation of the Latin text “Memento Mori”, the fundamental concept of stoicism, which treats death as something natural to be elaborated during life and which was used as a greeting by the hermits of Saint Paul in France (1620 – 1633).

A third example occurred from the skull of Luzia – one of the oldest human remains found in South America, dated at about 11,500 years -, discovered in Brazil in the region of the state of Minas Gerais in the early 1970s (Fig. 9). The ashes of the site where the piece was stored were separated and mixed with the 3D printing material, so that the model kept reminiscences of itself. Those who were in the presence of these new objects certainly did not place themselves with disinterest because they came from originals or wreckage. There is something added to them that allows you to answer the question by Bruno Latour & Adam Lowe (2020, p. 39), regarding whether it is possible to add something to the copy. Perhaps this objective has been achieved when we become aware of the origin and properties of the materials that constitute them and the constructive processes brought together for this. We are engaged in the effort of not allowing ruins to become only rubble.

It is still very hard to deal with the emptiness that the National museum has left for a country with so many problems and contrasts like Brazil. However, we understand that this is not an isolated phenomenon. The world beautifully seems to be using fire as never before, not to build, but to destroy. Legends say that the Chinese used gunpowder to scare away evil spirits with their fireworks, not for the primary purpose of building weapons. This was perhaps one of the wrong curves that humanity took when in the power of something entrusted only to the gods, it chose to prioritize it for domination.

“We were there anesthetized, hypnotized and enchanted by the strobe effect of the plumes we produced. They are friendly to the eye, they are the fruit of our efforts. But we forget that there is a second function in the tail / creation, which only occurs in its aerodynamic disappearance. Which is to make flight possible, evasion. The detachment with the soil. Make the impossible possible.”

Galeano, 2011

Photography is born and dies by light. The forger’s drawings were thrown at the stake, entire collections of a scientific institution were lost in a fire, extreme governments launched ideas and acts against their populations and nature, which smog on the future of the planet’s life. The excess of everything blinded us to the simple beauty and we were amazed only by the voracious spectacles. Walter Benjamin lived in an extremely sad moment in the history of his country, he had a tragic destiny during the Second World War, but he dedicated a large part of his work to the effort not to extinguish the welcoming flame of poetry from us.

3D printed models made of a mixture of polyamide and the ashes form the fire of the Museu Nacional.

For this reason, the myths related to this element were so important. Dibutades, Prometheus, Hephaestus and the Phoenix are internal stages of our own inner illumination. We start with the limited understanding of the shadows, then contact with the one who delivers the pyre of work to men, but is severely punished for his act, going through what seeks in concentrated metallurgy to create a world and, finally, the bird that is reborn from its combustion itself, demonstrating that the ends are restarting. Eduardo Galeano (1940-2015), Uruguayan journalist and writer, stated that in the human zoo, the breeders probably live in the peacock cage. We were there anesthetized, hypnotized and enchanted by the strobe effect of the plumes we produced.

Perhaps if we manage to accept that the only constant is inconstancy, we will have found the means to take a long look at the path we have traveled, admire its beauty and tragedies and understand that the despair contemplated at the limit of blindness is the manifestation of the clamor of time for renewal. When we disappear, our achievements will remain for a while longer. Stone work, in pain and love will endure, but not forever, everything will at some point be lost by the natural wear and tear of things, by natural tragedies or by the countless faces of war. Nothing will be spared, triumphs or frauds will turn to ashes. This is the fact of life. What’s left then? Continue to sing, delight with your eyes and write with the feather of the imperial bird, what has always been available for consultation in the firmament. •

References

Benjamin, W. (2012). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Scottsdale.

Charney, N. (2015). The Art of Forgery: The Minds, Motives and Methods of the Master Forgers – Phaidon, UK.

Dubois, P. (1990). L’acte photographique et autres essais – Nathan, Paris, France.

F for Fake (1973). Directed by Orson Wells, France, Janus Films (89 min.) Available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4C2nt72h0cQ (visited 24/04/2025)

Flusser, V. (1999). The Shape of Things – A Philosophy of Design, Reaktion Books, UK.

Galeano, E. 2011. Entrevista – Eduardo Galeano. Available on https://maisqueousual.wordpress.com/2011/03/29/entrevista-eduardo-galeano/ (visited 24/04/2025).

Irving, C. (1969). Fake: the story of Elmyr de Hory: the greatest art forger of our time. McGraw-Hill, USA.

Latour, B. & Lowe, A. (2020). The migration of the aura, or how to explore the original through its facsimiles. In: The Aura in the Age of Digital Materiality – Exhibition “La Riscoperta Di Un Capolavora” – Palazzo Fava, Bologna, 2020 – Silvana Editoriale, Milano. p. 33-42.

Lopes, J.; Azevedo, S. A.; Werner Jr., H. & Brancaglion Jr. A., 2019. Seen/Unseen: 3D visualization. 2019. Rio Books, Rio de Janeiro, 247 p.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 1961 (trans. H. Rackham), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, vol. 1.

Sennett, R. (2008). The Craftsman – Yale University Press, London, UK.