The digital epigraphy of the scene of Neferhotep’s Funerary Procession was developed during the 2020 and 2023 campaigns for the Proyecto de Conservación e Investigación de la tumba de Neferhotep (TT49), a site located in the Theban Necropolis of the Nobles, on the hill of El-Khokha (Luxor, Egypt).

Digital epigraphy is a way of producing a systematic record of the images and texts inscribed on the walls of the tomb, and the aim was to produce an updated vectorized drawing corresponding to the original image, according to the current preservation conditions of the scene.

The tomb dates from the short reign of Ay (1327-1323 BC), and its architectural style is characteristic of the late 18th Dynasty. Internally, it consists of a chapel and a vestibule and their respective access passages. Neferhotep was an employee of the temple of Karnak, and scenes related to his life, as well as funerary rituals, decorate his tomb. The entire scene we are dealing with here – the crossing of the Nile, the disembarkation, and the arrival on land at the tomb – is located on the east wall of the vestibule, extending from the north to the south of the upper register of this wall.

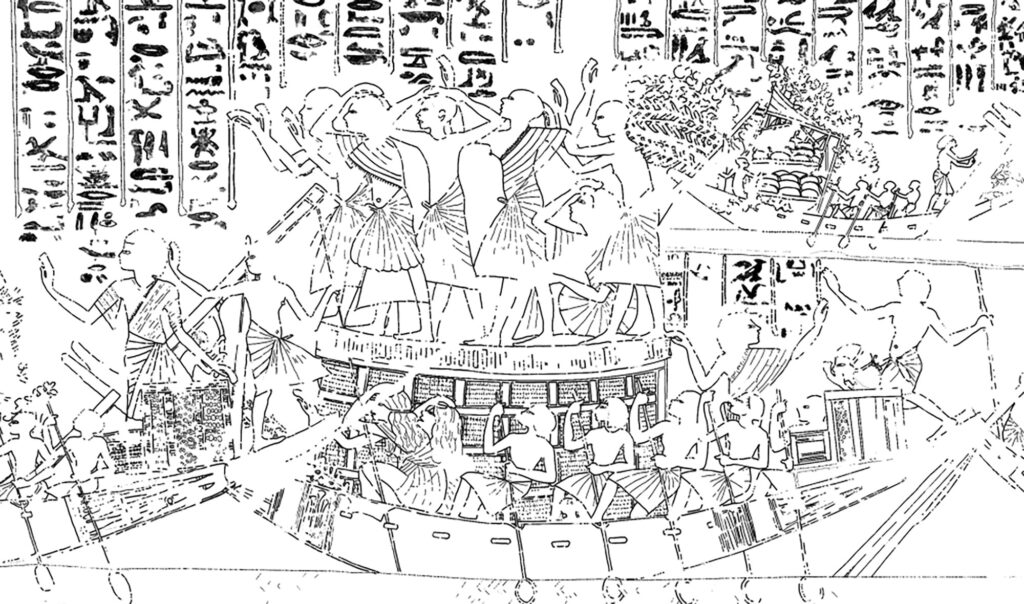

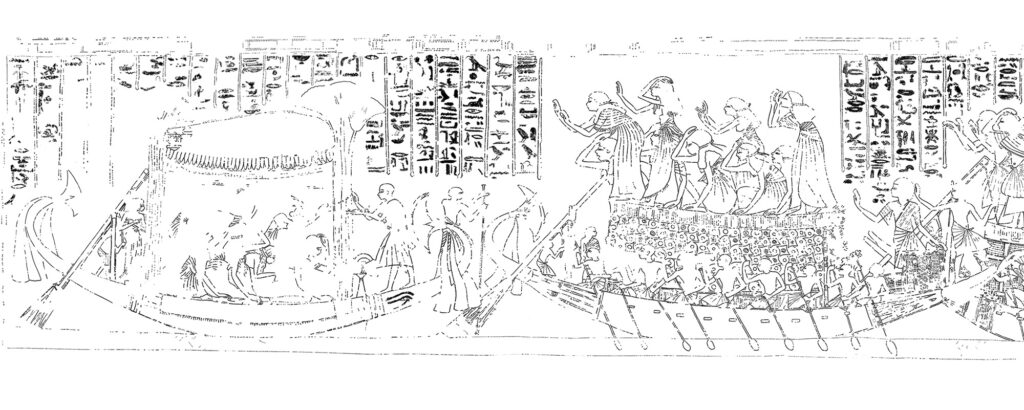

Like the entire decorative program of the tomb, it is a scene rich in detail and with an iconography of significant intent. In the spotlight, we see the boats crossing the Nile – six in all – presented in different dimensions, each carrying different characters and objects and representing different iconographic elements. They suggest the perception of movement and represent the crossing of the deceased to the west bank, the site of the necropolis, associated with the world of the dead.

At the left end of the scene, the first boat carries Neferhotep’s catafalque, which is mourned by some women, including his wife, Merytra. We identify this boat as the mythical Neshmet boat, whose crew assimilates divine functional roles. The second boat, manned by nine rowers, drags the first, and its cabin is filled with mourners, a similar theme to the next boat, which carries a group of mourning men. The other two boats carry the funeral furniture, the food needed for the funeral ceremonies, and members of the community heading for the tomb, the priests, relatives, and acquaintances of the deceased. In the final shot of the scene, we see the procession of the deceased and the mummified Neferhotep himself, on land, on the west bank; everyone stands in front of his tomb to pay their last respects and to celebrate the funeral rites.

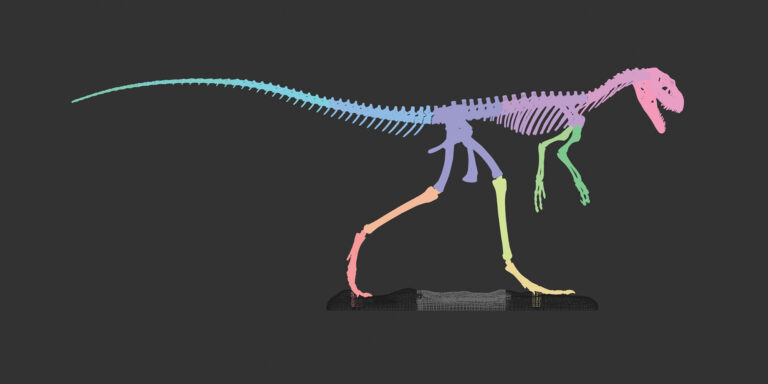

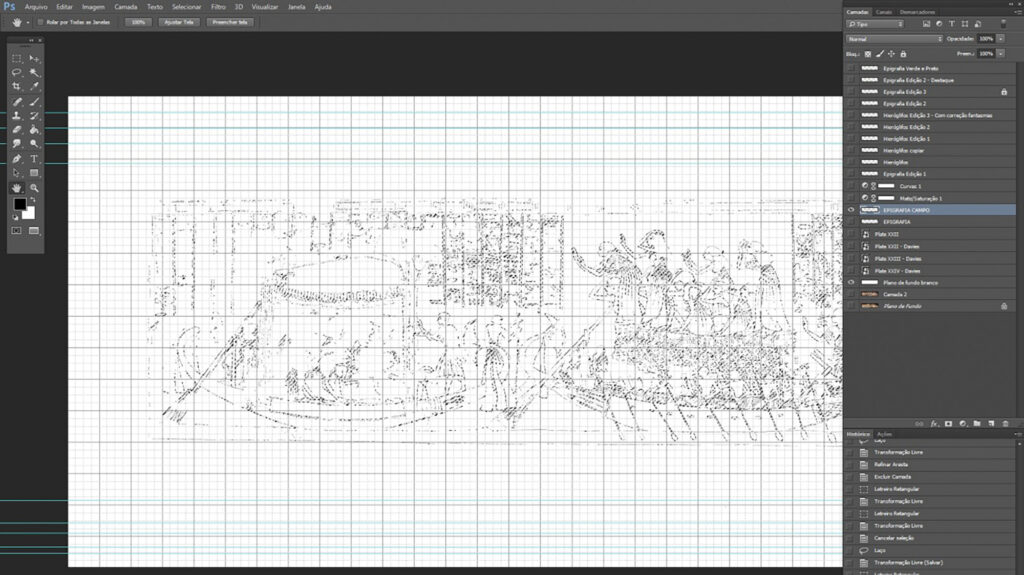

The production methodology consisted of different stages. Firstly, the first version of the digital epigraphy was developed using the photogrammetry of the scene produced by Víctor Capuchio and the epigraphy produced by Davies in the 1930s as the main reference (Figure 1). The drawings were made using a Wacom Intuos Pro tablet (model: PTH660) and the Adobe Photoshop CC program (version 2015.0.0). The program used different layers superimposed on the photogrammetry to produce the digital epigraphy. It was produced by visualizing the discrimination of the pixels according to the chromatic range presented by the photogrammetry. This method allowed us to verify the pigments that corresponded to the lines in the drawings and the hieroglyphics of the funeral procession scene.

The epigraphy was mainly produced using freehand strokes, using the brush tool, and in straight areas, using the pen tool. These strokes and lines were guided by the overlapping of the lines identified in the image. The use of layers with alterations to the hue and saturation of the photogrammetry colors also helped to visualize and identify the elements of the scene.

The fieldwork consisted of checking the digital epigraphic drawing in situ, using different methodologies. The drawing made from photogrammetry needed to be fixed because it had mistakes. It also needed some details added that were noticed on site (Figure 2). The first step consisted of measuring the scene and different elements of the scene using a manual scale, tape measure, L3D-12 Arita digital level, and the GLM 120 C Bosch digital tape measure. We used these tools without direct contact with the wall, preventing any damage to the highly fragile mural paintings (Figures 3).

From the on-site measurements, it was possible to understand the proportions of the linear measurements of the drawing and establish a scale applicable to the epigraphic work. This scale made it possible to make the necessary corrections to the drawing using the Adobe Photoshop program, which were done with the Wacom pen and tablet, starting from the freehand tracing. The iconography and hieroglyphs were checked in parts, based on direct observation of the chosen section of the scene, such as the image of the men’s choir boat (Figure 4).

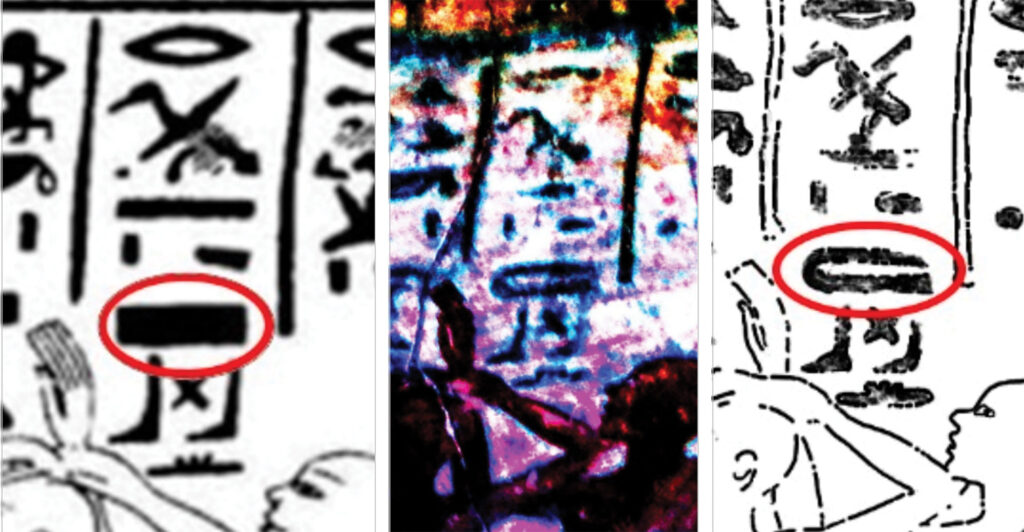

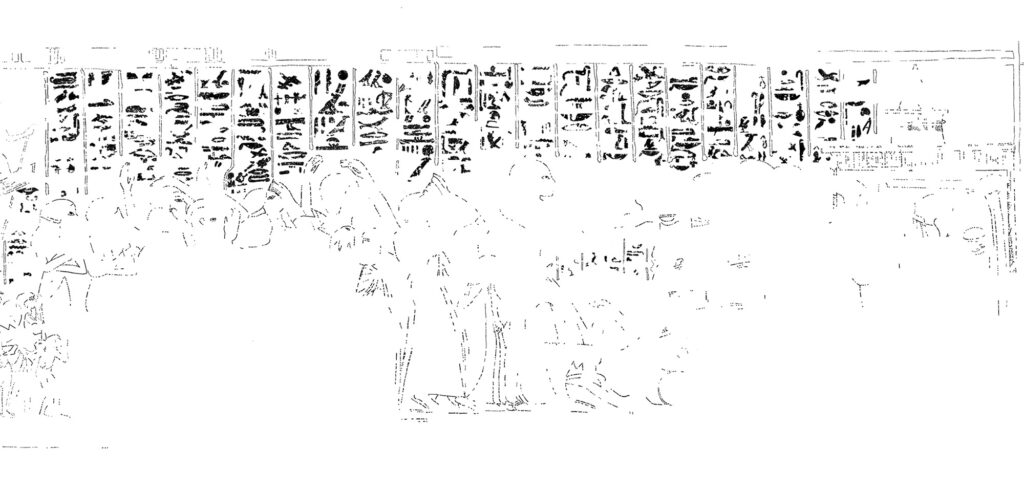

Several areas of the scene and many of the inscriptions have worn away, making it difficult to interpret the elements and hieroglyphs, often making it impossible to represent them in epigraphy. Due to the wear and tear of many signs, distinguishing between pigments and signs of wear and tear requires painstaking work to verify and reproduce the inscriptions more reliably. By observing them in situ and looking at the photos taken with UV light (Figure 5), it was possible to compare and verify some hieroglyphs that raised doubts about their identification (Figure 6).

The post-field activities consisted of altering the distortions according to the proportions verified in situ. Through measurements, it was possible to see some patterns in the heights and widths of the images and thus check the relative scales of the drawing. The distortions were altered using the Photoshop transformation tool and by framing the epigraphy according to the relative measurements between height and width (Figure 7).

As a result of these different methodologies, it was possible to produce a digital epigraph of the funeral procession scene by translating the image on the wall into a vectorized image. The distortion corrections sought to respect the perspective of the scene captured by direct observation. The corrections to the various elements of the scene and the designs and shapes of the hieroglyphs also sought to follow the patterns of the images observed in the field through the different resources used, resulting in an epigraphic work produced with different image control and perception resources (Figures 8, 9 and 10).

References

DAVIES, N. de G., 1973. The Tomb of Neferhotep at Thebes. 2 vols. (Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition, New York: Arno Press.

PEREYRA, M. V.; ALZOGARAY, N.; ZINGARELLI, A.; FANTECHI, S.; VERA, S. VERBEEK, C.; GRAUE, B.; BRINKMANN, S., 2006. Imágenes a preservar en la tumba de Neferhotep. Tucumán: Facultad de Artes, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán.

PEREYRA, M. V.; BONANNO, M.; CATANIA, M. S.; IAMARINO, M. L.; OJEDA, V. C.; CORDEIRO, E. S. N.; LOVECKY, G. A., 2019. Neferhotep y su espacio funerario I. Ritual y programa decorativo. Buenos Aires: IMHICIHU – CONICET.

WILKINSON, R. H., 1992. Reading Egyptian Art. A hieroglyphic guide to ancient Egyptian painting and sculpture. New York: Thames and Hudson.