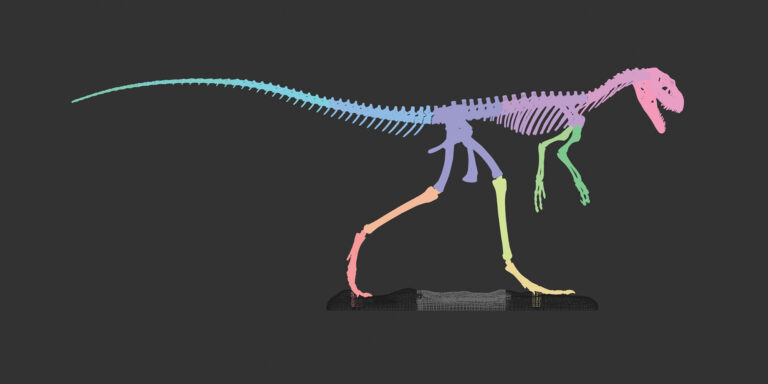

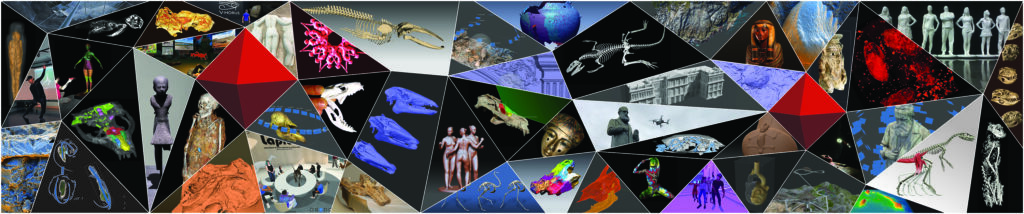

The use of three-dimensional technologies by the Digital Image Processing Laboratory (LAPID) is not a result of recent events, such as the fire at the National Museum in 2018 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Since the early 21st century, LAPID has been employing three-dimensional technologies and tools for research, teaching, and extension activities in fields such as paleontology, zoology, geology, archaeology, and other areas of knowledge. These activities are well-documented in dissertations, theses, articles, and book chapters published by laboratory members over the past 20 years (notably in WERNER Jr. & LOPES, 2009 and LOPES et al. 2013). Therefore, the use of these technologies and methodologies in LAPID’s research has a long-standing tradition (Figure 1).

The year 2018 was marked by a devastating fire in the main building of the National Museum, the former Palace of the Imperial Family. This building housed not only LAPID but also numerous other laboratories, collections, and exhibitions, all of which were severely impacted by the fire (RODRIGUES-CARVALHO et al., 2022). The fire annihilated all of LAPID’s equipment and the materials under analysis at the time; some items were completely lost, while others were significantly damaged. As a result, in addition to losing its three-dimensional technology equipment, the collections previously accessed by LAPID members for study became inaccessible. In response, the laboratory acted on two fronts: (1) employing more accessible 3D technologies, such as photogrammetry, to record the rescue of specimens buried by the fire and (2) utilizing already digitized specimens to continue research, particularly those related to ongoing theses, and for teaching and extension activities, by prototyping them with various materials (some of this work can be seen in LOPES et al. 2019). Therefore, until the COVID-19 pandemic hit Brazil in early 2020, LAPID members were primarily focused on rescuing collections affected by the fire, particularly the paleontology collection, though not exclusively. They also worked to reconstruct the database of digitized specimens and further advanced the use of 3D technologies in research (for an overview, see GRILLO et al. 2020).

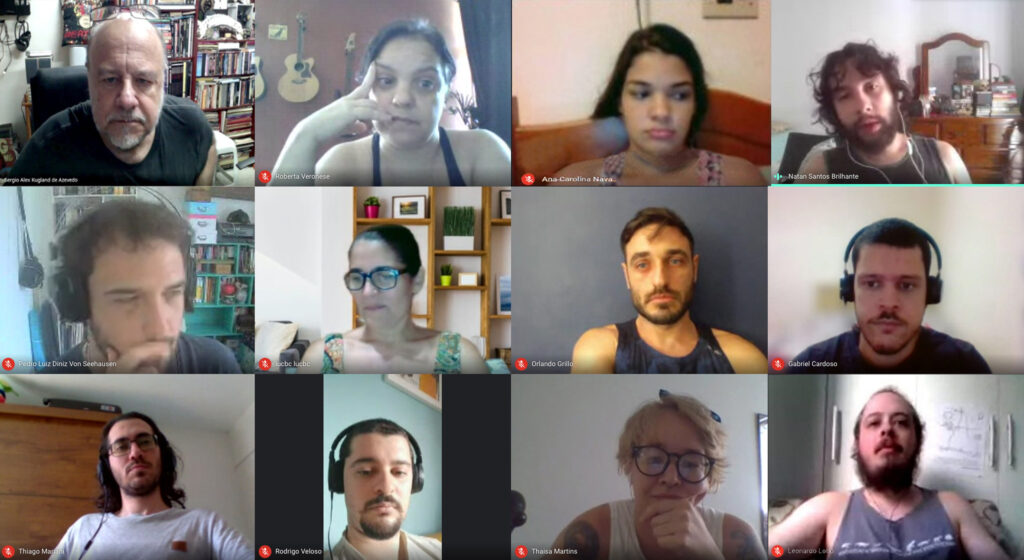

By early 2020, LAPID still lacked its own physical space; its members were working in various partner laboratories that had not been affected by the fire, such as the Laboratory of Three-Dimensional Models (LAMOT) of the Instituto Nacional de Tecnologia and the Laboratory of Mastozoology of the Museu Nacional. The emergence and rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 brought about a drastic shift in global reality. To contain the virus, governments implemented widespread restrictions, including border closures and severe limitations on movement, which profoundly impacted daily life (PEERI et al., 2020). Such measures were no different for researchers, so LAPID, like all other laboratories, implemented rotating shifts for essential in-person work and shifted much of its research activities to remote work (Figure 2).

Given the above-described events —the loss of specimens, which equates to the loss of cultural heritage and its geometric information, as well as the near-total restriction on mobility that prevents access to specimens unaffected by the fire or housed in other institutions—the daily scientific progress of any natural science laboratory and related fields was directly impacted. In response, some LAPID members focused on exploring how digital techniques and methodologies could facilitate digital access to these materials, thereby enabling the continuation of scientific research. They identified the most suitable three-dimensional techniques for the materials and the technological realities of Brazilian institutions, outlined strategies for prioritizing specimens (particularly those from zoological collections), and explored potential funding opportunities(LOBO et al. 2021). It is also important to note that travel restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic could potentially be reinstated in the future, as the possibility of future pandemics remains a concern (CYRANOSKI, 2020).

Considering this type of scenario and the importance of accessing scientific information contained within the collections of various research institutions worldwide, finding new ways to make three-dimensional morphological data available has become increasingly important, similar to the ongoing debate about the availability of associated data, i.e. metadata (OECD, 1999). Remote access through digital databases offers several advantages, such as minimizing the need for researchers to travel to visit difficult-to-access collections, enhancing the dissemination of scientific information, and facilitating comparisons between different specimens. Additionally, digital archives allow researchers to access necessary information without handling fragile and rare specimens.

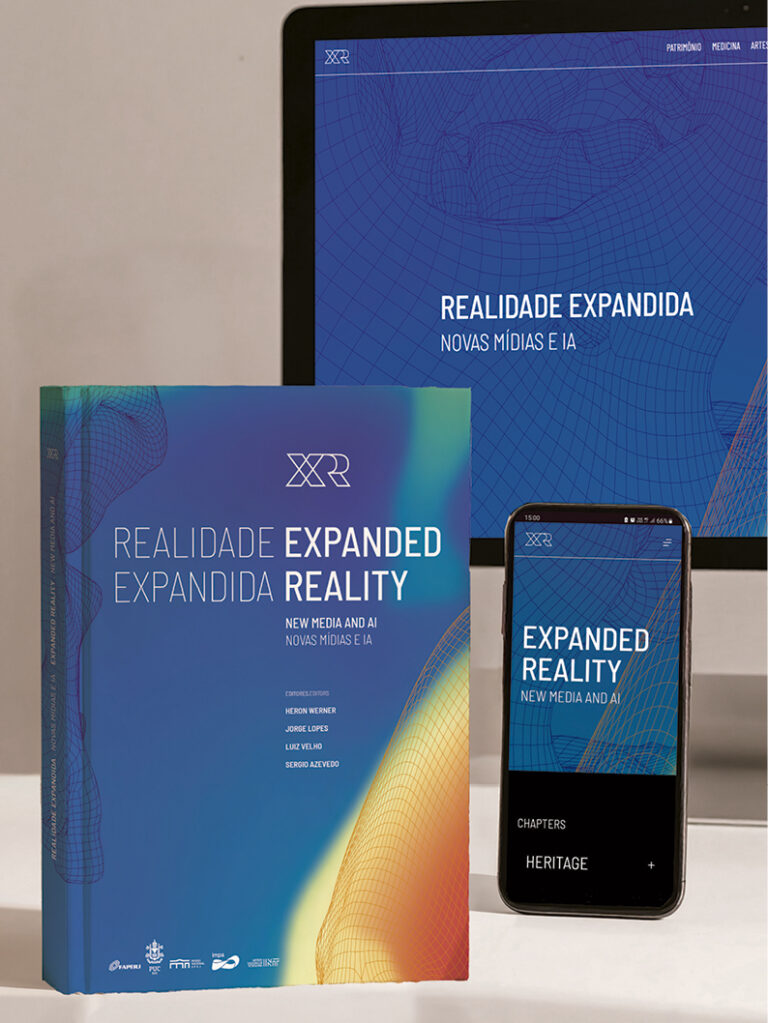

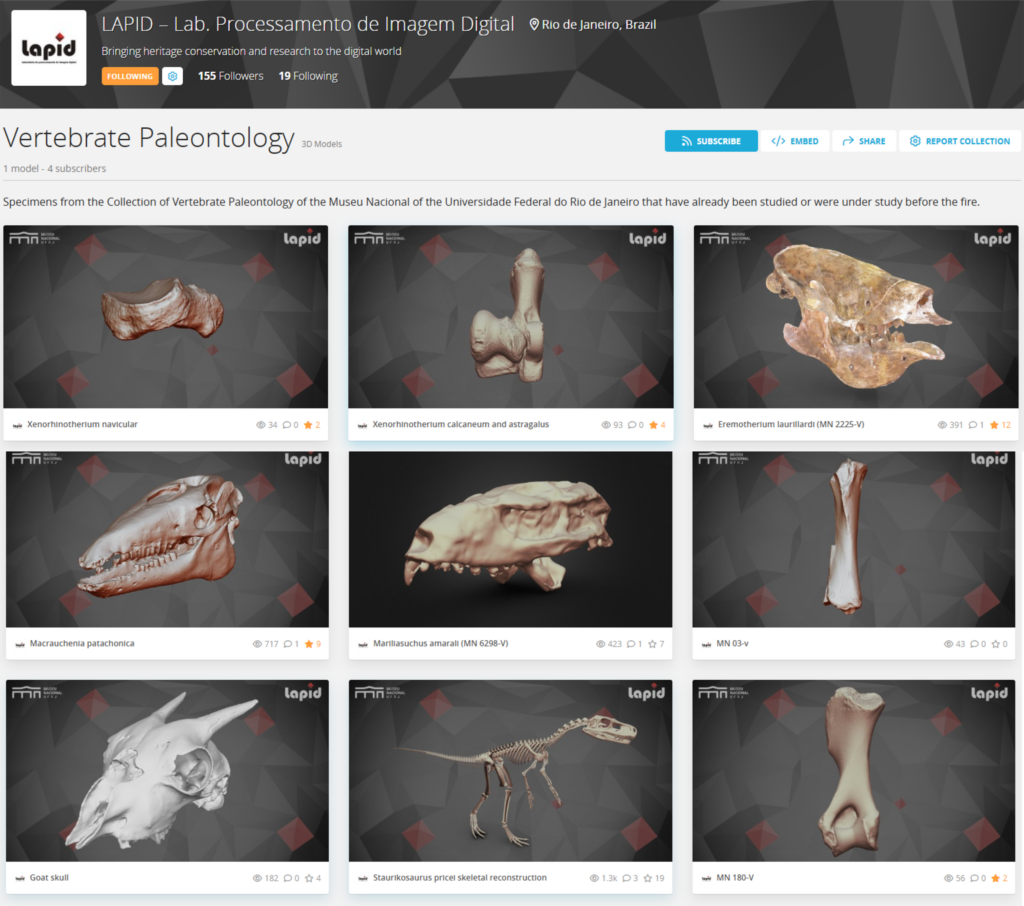

Several institutions have been working to digitize their scientific collections and make them accessible through online databases. Platforms such as Morphobank, DigitalMorphology, MorphoSource, and MorphoMuseum have been used, alongside institutions’ platforms, such as the Smithsonian Institution’s X3D. These platforms cater to researchers who need to request access to data similarly to how they would when visiting a scientific collection in person. Another widely used platform, but for public availability, is Sketchfab, which allows 3D models to be made available for viewing only or download at the curators’ discretion. During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, LAPID focused initially on virtual curation to organize its three-dimensional data, discuss availability policies, create accounts on platforms, e.g. https://sketchfab.com/lapid.mn (Figure 3), and make morphological data available in publications (LOBO et al. 2021) (Figure 4).

Unfortunately, the 3D digitization process of collections is very time-consuming and requires a specialized team dedicated to this work. The digitization of a single piece can take from a few hours to several days, depending on the complexity of the material and the need for post-processing. To put this into perspective, digitizing a collection with 10,000 items would take approximately 40 years of continuous work if it were possible to digitize and make available one item per day. Some institution’s collections have more than 200,000 items.

Therefore, while the digital availability of collections offers benefits, it also presents new challenges for research institutions. These challenges include the need to discuss policies for access to digital archives, define standards and documents for data management and treatment, determine how visitors can use the data, etc. The digitization process itself introduces a series of challenges, such as the need for reliable, secure, and high-capacity storage devices, backup copies on online servers, fast internet connections to handle large amounts of data, hiring new technicians dedicated to digitizing and processing files, etc. As a result, there is a constant demand for more financial resources since these methodologies have high implementation costs. Even with investment through support notices from financing agencies, Brazil’s level of investment remains far below what is necessary, especially when compared to its historical series, remaining below 2014 levels (SOU CIÊNCIA, 2024). Currently, Brazil uses slightly more than 1% of its Gross Domestic Product in technology development, which is relatively low when compared to the countries leading in this area, such as Germany (3.1%), China (2.4%), the United States of America (3.5%), and Japan (3.3%). (OUR WORLD IN DATA, 2025).

Despite these challenges, digitizing collections creates countless possibilities for research and outreach. As the pandemic progressed, LAPID members maintained curatorial activities and heritage discussions using three-dimensional technologies within the implemented distancing measures and focused on virtual reality technologies and platforms. One interesting use of these technologies is the creation of digital virtual exhibitions that can be visited by anyone from anywhere in the world. Using virtual reality platforms, such as Spatial.io, and a set of virtualized three-dimensional models accumulated over two decades of work, coupled with new modeling possibilities provided by new software, LAPID members developed virtual exhibitions. These exhibitions aim to enable a greater degree of immersion and interactivity between visitors and the collection, which was either inaccessible or had been lost during the fire. Thus, the team has been producing some initiatives on this topic through collaboration with colleagues from the Space-XR group (a collective that includes researchers from LAPID/Museu Nacional/UFRJ, VISGRAF/IMPA, BIODESIGN/PUC-Rio, and LAMOT/INT). More information about this project is presented in other chapters of this work.

Conclusion

The events of recent years have necessitated not only the continuation of research, teaching, and outreach by the Digital Image Processing Laboratory team but also deep reflections on LAPID’s role within the National Museum and as an institution that contributes to scientific progress. The fire at the National Museum and the distancing measures introduced by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic led us to explore several themes:

- How three-dimensional technologies can enhance the curation processes of Cultural Heritage safeguarded by scientific institutions.

- Reflections on which specimens should be prioritized in this extended curation process, given the limitations imposed by the number of specialized personnel and available equipment.

- The need to create a database that houses and enables access to three-dimensional models from scientific production as an essential part of the curation and dissemination of the scientific collections present at the institution.

- Development of new extension possibilities based on virtual immersion technologies, such as the creation of themed rooms to disseminate scientific information, especially in the context of the restoration process of the National Museum exhibition.

Finally, based on everything discussed, it is clear that there is a need to increase investment in science and technology and in research institutions This is crucial to enhance the capacity to respond appropriately to the challenges faced during the scientific and educational development of our country, creating opportunities for better-equipped research centers with more personnel to research and safeguard our Cultural Heritage.

References

CYRANOSKI, D. 2020. Profile of a killer: the complex biology powering the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01315-7.

GRILLO, O.; LOBO, L. & AZEVEDO, S. A. 2020. LAPID: Using 3D to Recover Heritage Lost in a Fire. https://sketchfab.com/blogs/community/lapid-using-3d-to-recover-heritage-lost-in-a-fire.

LOBO, L. S.; GRILLO, O. N. & AZEVEDO, S.A.K., 2021. Morfologia, Pandemia e 3D. Arquivos de Zoologia, 52(2): 33-40. http://doi.org/10.11606/2176-7793/2021.52.02.

LOBO, L. S.; SALLES, L. D. O. & MORAES NETO, C. R., 2021. 3D model related to the publication: A Puma concolor (Carnivora: Felidae) in the Middle-Late Holocene landscapes of the Brazilian Northeast (Bahia): submerged cave deposits and stable isotopes. MorphoMuseuM 7:156. doi: 10.18563/journal.m3.156

LOPES, J.; Brancaglion Jr., A.; Azevedo, S. A. & WERNER Jr., 2013. Tecnologia 3D: desvendando o passado, modelando o futuro. Editora Lexikon, 248 p.

LOPES, J.; AZEVEDO, S. A.; WERNER Jr., H. &, BRANCAGLION Jr., A. 2019. Seen/Unseen. RioBooks, Rio de Janeiro, 244 p.

PEERI, N.C.; SHRESTHA, N.; RAHMAN, M.S.; ZAKI, R.; TAN, Z.; BIBI, S.; BAGHDANZADEH, M.; AGHAMOHAMMADI, N.; ZHANG, W. & HAQUE, U. 2020. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID‑19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? International Journal of Epidemiology, 49(3): 717‑726.

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT (OECD). 1999. Final Report OECD Megascience Forum Working Group on Biological Informatics. OECD, Paris. Disponível: http://www.oecd.org/science/inno/2105199. pdf.

OUR WORLD IN DATA, 2025. Research & development spending as a share of GDP [dataset]. UNESCO Institute for Statistics, “World Development Indicators”. Acessado em 20/01/2025, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/research-spending-gdp. (acesso em 20/01/2025).

RODRIGUES-CARVALHO, C.; CARVALHO, L.; AMARAL, A. L.; REIS, S.; BITTAR, V., 2022. Depois das cinzas: Conservação preventiva das coleções recuperadas pelo Núcleo de Resgate de Acervos do Museu Nacional. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 104 p.

SOU CIÊNCIA, 2024. Orçamento das Universidades Federais. Acessado em 10/01/2025, disponível em https://souciencia.unifesp.br/dados-fctesp/orcamento-universidades-federais.

WERNER Jr., H. & LOPES, J., 2009. Tecnologias 3D: Paleontologia, Arqueologia e Fetologia. Editora Revinter, 202 p.