Fig1. Echoes of Plato’s Cave: A robot reaches toward the shadows in a luminous cave, drawing a parallel with Plato’s allegory and exploring the intersection of ancient allegory and modern technology in our quest for understanding our realities.

PREAMBLE: Revisiting Plato’s Cave in the Digital Age

Plato’s allegory of the cave (4th century BCE), shadows cast on a wall are perceived as reality by prisoners who have never seen the world outside. Today, this allegory holds renewed significance in our digital age, as we navigate immersive realms of the metaverse and virtual spaces. Here, shadows on the wall take the form of pixels and digital avatars, challenging our notions of reality and self-perception (fig1).

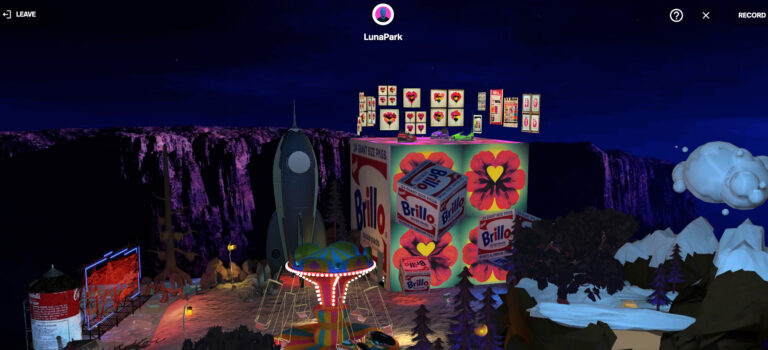

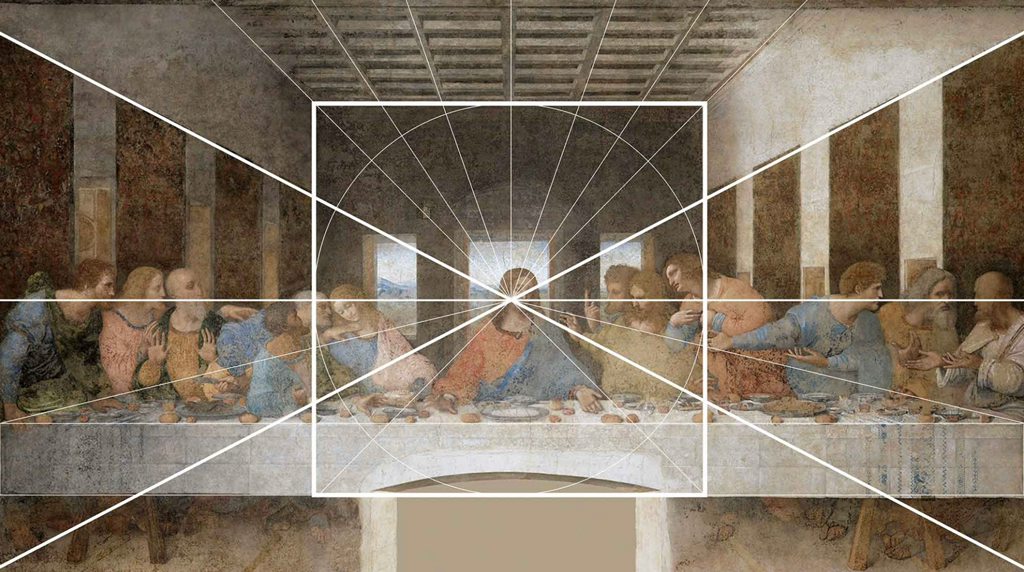

This manifesto proposes that, if used thoughtfully, the metaverse and related digital tools can become transformative spaces for authentic self-expression, ethical creativity, and social engagement. (fig2) As Michelangelo (1475–1564) and da (fig3) Vinci (1452–1519) used Renaissance art to explore the human experience, so can the metaverse expand our creative horizons, becoming a conduit for deeper connections. This digital presence should be active, aware, and rooted in the values of inclusivity, transparency, and artistic integrity.

01. Active Presence in Digital Spaces

Active presence implies intentional engagement with digital environments, where technology serves as a medium for human expression rather than a substitute for genuine interaction. Renaissance masters like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci employed artistic techniques to capture the depth of human emotion and the complexity of the natural world. (fig4) Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) and Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) epitomize this pursuit of capturing the essence of human presence and form.

(fig5) In the digital realm, active presence means that users are not merely passive recipients but active participants in crafting their digital experiences. Transparency in digital platforms is essential, as AI algorithms increasingly shape interactions. Just as Renaissance artists aspired to express human ideals, we must strive for digital environments that reflect our core values, prioritizing human agency, integrity, and trust.

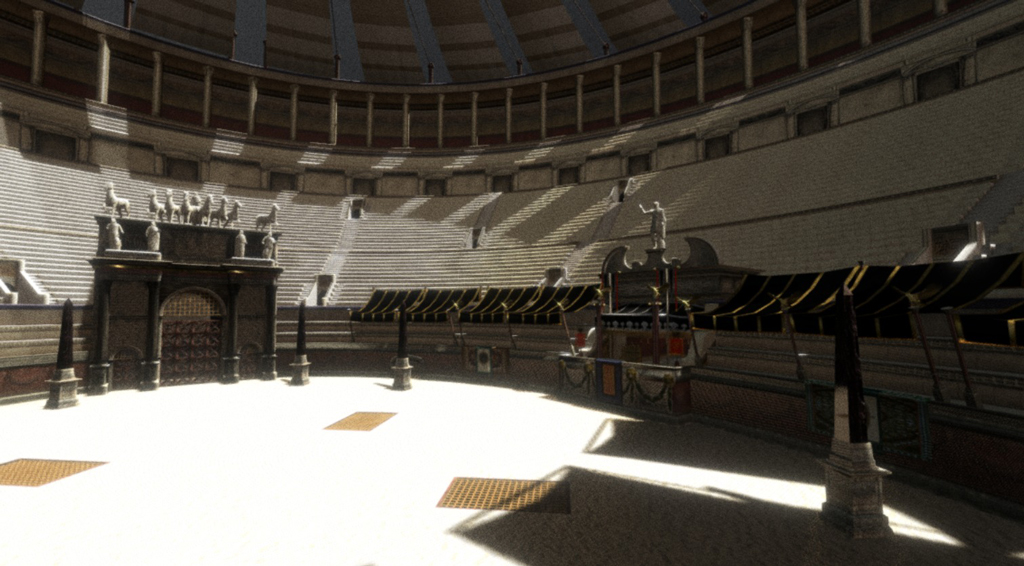

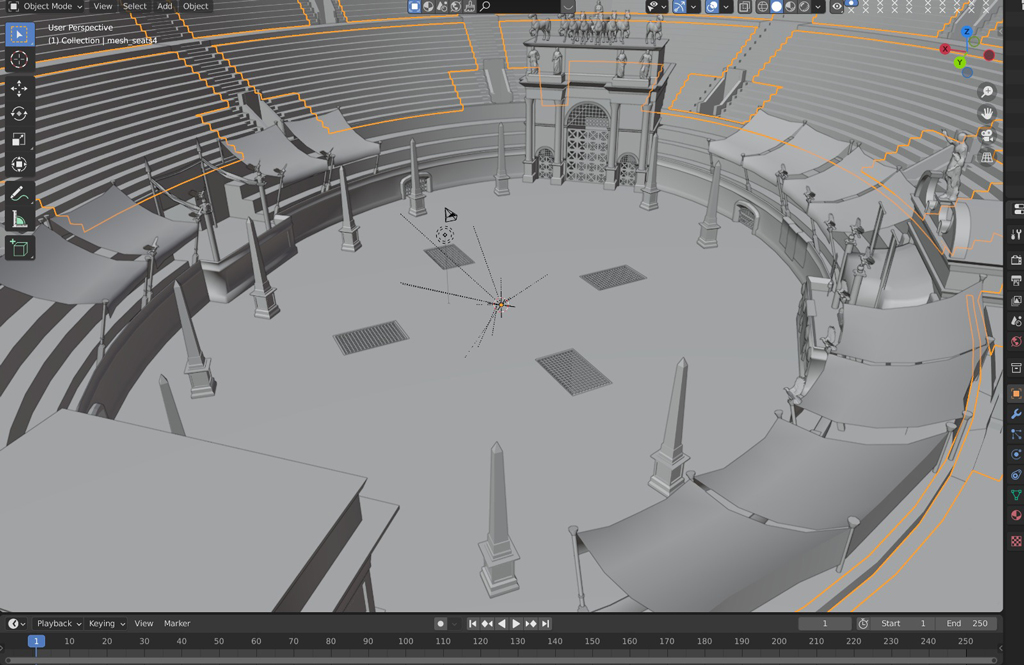

source: https://colosseum.social

source: https://colosseum.social

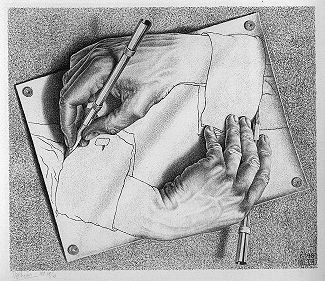

02. Art and Imagination: From Drawing Hands to Virtual Creativity

(fig6) Throughout history, artists have explored the boundaries of perception and reality. M.C. Escher’s Drawing Hands (1948), where two hands draw each other into existence, captures this concept of recursive creativity—a cycle of creation and reflection. In the metaverse, artists work with algorithms in a similar interplay, generating art that is both human and machine-made, expanding the concept of creative collaboration.

The Renaissance revolutionized art through innovations like linear perspective and chiaroscuro. Artists like Caravaggio (1571–1610) pushed these techniques further, introducing dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, as seen in works like (fig7) The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600). Today’s digital art builds on these principles, using real-time rendering and generative techniques to create immersive experiences that evolve with each interaction. This interplay between artist and algorithm mirrors the collaborative process of creation, offering a new realm for dynamic artistic expression.

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drawing_Hands

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Calling_of_Saint_Matthew#/media/File:The_Calling_of_Saint_Matthew-Caravaggo_(1599-1600).jpg

03. Viewer as Co-Creator: From Audience to Active Participant

Art’s evolution from a passive experience to one of active participation has historical roots. In the Baroque era, Bernini (1598–1680) designed sculptures and spaces, such as (fig8) The Rape of Proserpina (1621-1622), which engaged viewers by drawing them into the dramatic narratives depicted. Similarly, in the digital metaverse, the viewer transitions from an observer to an essential part of the creative process, shaping their experiences through choices and interactions.

The metaverse allows users to become co-creators, influencing the direction and nature of their experiences. This dynamic relationship between the viewer and art mirrors (fig9) the 20th-century Fluxus movement, where artists like Yoko Ono invited the audience to complete the artwork. In digital environments, the viewer’s engagement feeds back into the artwork itself, creating a living, evolving entity shaped by each interaction.

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rape_of_Proserpina

source:https://historyofourworld.wordpress.com/2009/12/02/fluxus-fluxus-1995/

04. The Convergence of Virtual and Physical Realities

The metaverse represents an integration of the digital with the physical, where virtual elements blend with tangible reality to create new forms of interaction. (fig10) Renaissance architects like Borromini (1599–1667) and Bramante (1444–1514) used mathematical precision to create spaces that guided the viewer’s experience. Borromini’s work, particularly in San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1638–1641), exemplifies this precision and play with space, guiding the observer’s movement and vision.

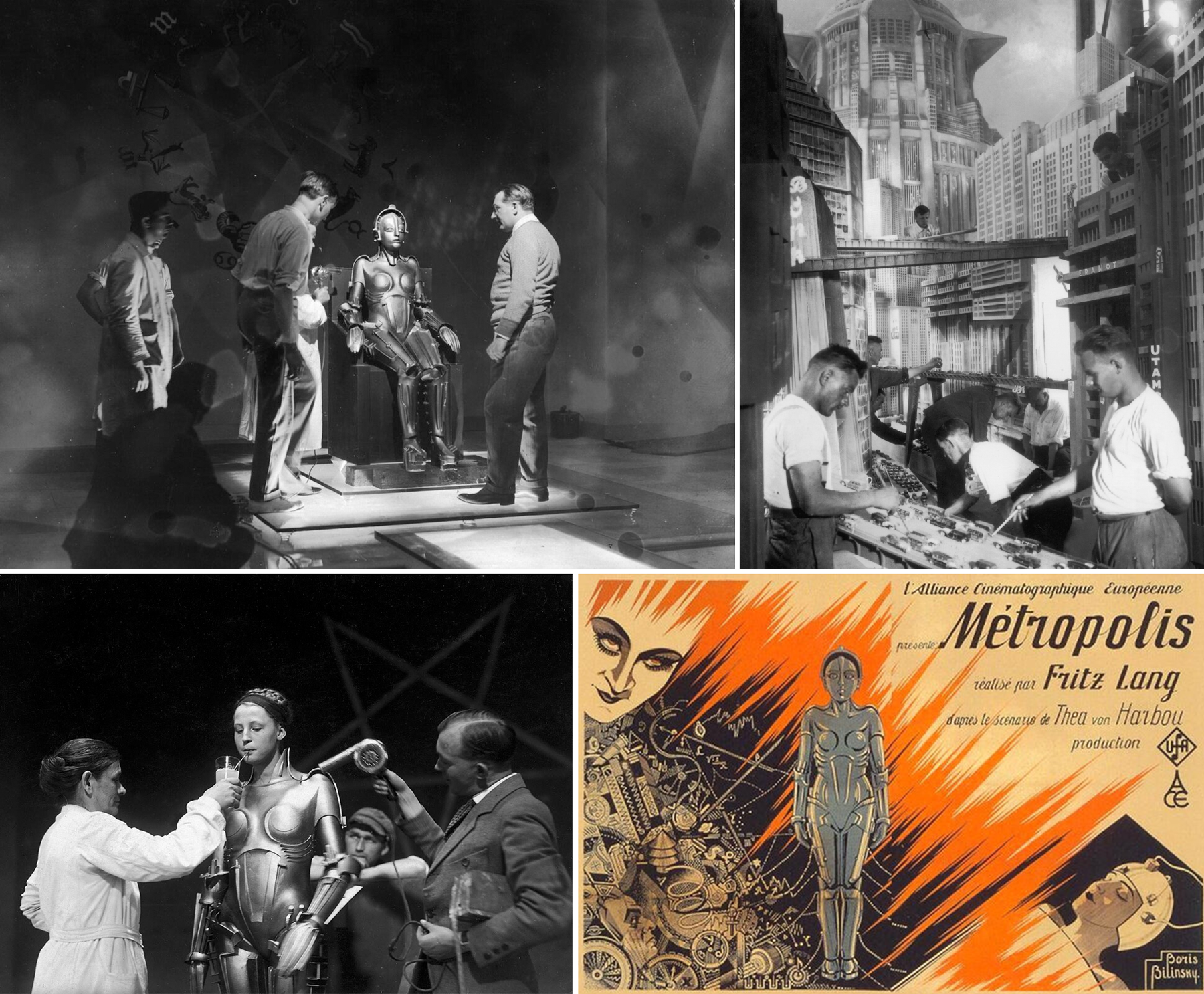

Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) offer even more immersive experiences, echoing the pioneering visions of filmmakers like Fritz Lang (1890–1976) in (fig11) Metropolis (1927), who imagined cities blending futuristic and realistic elements. The convergence of digital and physical realms invites us to reconsider the spaces we inhabit, as AR enriches our surroundings with layers of art, information, and expression.

source:https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiesa_di_San_Carlo_alle_Quattro_Fontane#/media/File:San_Carlo_alle_Quattro_Fontane_(Rome)_-_Dome.jpg

source: https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/rtf-architectural-reviews/a6188-an-architectural-review-of-metropolis-1927/

05. Ethical Considerations: Identity, Ownership, and Privacy in the Digital Realm

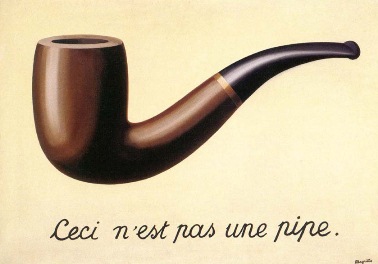

The rise of digital identities, avatars, and virtual assets introduces questions of ownership, privacy, and authenticity. Artists like René Magritte (1898–1967) challenged concepts of representation with works such as The Treachery of Images (1929), reminding viewers that a representation is not the object itself. This tension is echoed in digital spaces, where avatars are both extensions and abstractions of the self. (fig12)

Blockchain technology provides new avenues for ownership and authenticity in digital art, allowing creators to retain control over their works. Yet, as digital environments evolve, we must ensure that privacy is maintained, and users’ rights to define and protect their identities are upheld. The ethical questions raised by Magritte about representation resonate deeply in today’s digital landscape, encouraging us to safeguard authenticity and individual autonomy.

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images#/media/File:MagrittePipe.jpg

06. Inclusivity and Accessibility: Designing Equitable Digital Spaces

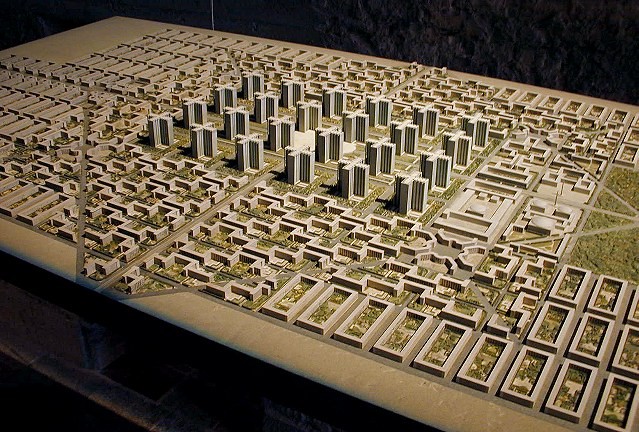

(fig13) In physical spaces, architects like Le Corbusier (1887–1965) emphasized functionality and accessibility. His designs aimed to serve diverse communities, embedding social utility into architecture. This commitment to inclusivity must extend to digital spaces, where design should prioritize accessibility for all. (fig14)

Digital inclusivity means crafting environments that accommodate various abilities, cultural backgrounds, and identities. Avatars, interfaces, and virtual spaces must be designed to enable participation by people of all backgrounds and abilities. By adopting inclusive design principles, the metaverse becomes a space where diversity thrives and social equity is promoted, echoing the Bauhaus movement’s commitment to accessible, socially aware design.

source: https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/787030/classicos-da-arquitetura-ville-radieuse-le-corbusier

07. Sustainability in the Digital Age: Inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement

(fig15) The environmental impact of digital technology is significant, and the metaverse’s infrastructure requires careful management. The Arts and Crafts movement, led by figures like William Morris (1834–1896), emphasized sustainable practices and the value of craftsmanship. Today, the energy demands of data centers, blockchain systems, and digital production highlight the need for an environmentally conscious approach to virtual worlds.

Sustainable design in the metaverse involves energy-efficient technologies and eco-friendly infrastructure. By prioritizing green energy and reducing digital waste, the metaverse can serve as a model for environmentally responsible development. This approach ensures that the digital future respects and preserves our natural resources, honoring the environmental ethos of movements like Arts and Crafts.

08. Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration: A Renaissance for the Digital Age

The Renaissance was a period of intense cross-disciplinary collaboration, where artists, scientists, and thinkers like da Vinci fused knowledge from various fields to create groundbreaking works. Today, the metaverse brings together experts from computer science, visual arts, psychology, and philosophy to craft immersive digital experiences.

This collaborative spirit enables the metaverse to transcend its entertainment origins, becoming a platform for education, healthcare, and artistic exploration. By embracing a cross-disciplinary approach, the metaverse reflects the Renaissance ideal of blending art and science to enrich human experience and understanding. (fig16)

09. Toward a Responsible Digital Future

(fig17) As architects of the metaverse, we bear the responsibility of shaping a future that upholds transparency, inclusivity, and ethical engagement. Just as Enlightenment thinkers like Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) championed reason and autonomy, today’s digital architects must ensure that the metaverse serves the public good, protecting user rights and fostering trust.

A responsible digital future respects individual privacy, promotes ethical design, and encourages inclusive participation. In this vision, the metaverse is not just a platform but a shared space that enhances creativity, connection, and personal growth, inviting users to explore new dimensions while remaining grounded in human values.

Conclusion: The Metaverse as a New Canvas for Human Imagination. Toward a Responsible Digital Future

(fig18) The metaverse represents a new canvas for artistic and social exploration, offering possibilities for creativity, interaction, and connection that are as transformative as the invention of the printing press or the rise of cinema. Like Plato’s prisoners, we stand at the entrance of a new reality where digital spaces can either confine or expand our understanding of self and society.

This manifesto envisions a metaverse that reflects the highest aspirations of art and society—one that is vibrant, inclusive, and fundamentally human. By promoting active presence, embracing ethical practices, and fostering sustainable innovation, we can shape a digital future that honors the depth of human creativity and the richness of shared experience. As R. Buckminster Fuller said, “We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims.”

Let us, therefore, build a metaverse that empowers, inspires, and unites, transforming this digital realm into a powerful force for collective growth and imagination. To achieve this, we must suspend disbelief, open our minds to this new dimension, and allow it to become a space of real meaning and true presence. Just as the Città Ideale paintings once envisioned an idealized, harmonious urban landscape, we can strive to construct a metaverse that embodies our highest ideals and aspirations—a digital città ideale for a connected age.

References

1. Plato. The Republic. Translated by G.M.A. Grube, Revised by C.D.C. Reeve, Hackett Publishing Company, 1992. Originally composed around 380 BC.

2. Michelangelo Buonarroti. Various works and contributions to Renaissance art, 1475–1564.

3. Leonardo da Vinci. Notebooks. Edited by Irma A. Richter, Oxford University Press, 2008. Originally composed 1452–1519.

4. Escher, M.C. Drawing Hands. Lithograph, 1948.

5. Caravaggio. The Calling of Saint Matthew. Oil on canvas, Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, 1599–1600.

6. Bernini, Gian Lorenzo. The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. Marble sculpture, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, 1647–1652.

7. Ono, Yoko. Contributions to the Fluxus movement, performances and artworks, circa 1960s.

8. Lang, Fritz. Metropolis. Film directed by Fritz Lang, Universum Film AG, 1927.

9. Magritte, René. The Treachery of Images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe). Oil on canvas, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1929.

10.Le Corbusier. Various principles of modern architecture, writings and buildings, 1887–1965.

11. Morris, William. Key writings and contributions to the Arts and Crafts movement, late 19th century

12. Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Norman Kemp Smith, Macmillan, 1929. Originally published in 1781.

13. https://www.artesvelata.it/citta-ideale-leon-battista-alberti/